- Home

- Fergus Hume

The Solitary Farm

The Solitary Farm Read online

Produced by Suzanne Shell, Mary Meehan and the OnlineDistributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Thisfile was produced from images generously made availableby The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

The Solitary Farm

BY FERGUS HUME

AUTHOR OF "THE MYSTERY OF A HANSOM CAB," "THE SACRED HERB," "THE SEALEDMESSAGE," "THE GREEN MUMMY," "THE OPAL SERPENT," "THE RED WINDOW," "THEYELLOW HOLLY," ETC., ETC., ETC.

G. W. DILLINGHAM COMPANY PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Copyright 1909 by G. W. DILLINGHAM COMPANY

_The Solitary Farm_

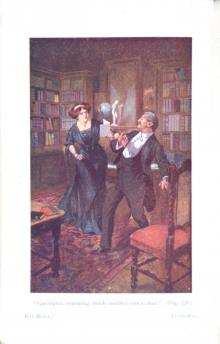

AS BELLA RAN INTO HIS ARMS HE DRAGGED HER INTO THESTANDING CORN.]

CONTENTS

I. THE DOMAIN OF CERES

II. THE WOOIN' O'T

III. THE TARDY LOVER

IV. SUDDEN DEATH

V. A MYSTERIOUS CRIME

VI. THE INQUEST

VII. CYRIL AND BELLA

VIII. THE WITCH-WIFE

IX. THE COMING OF DURGO

X. A LOVER'S MEETING

XI. A RECOGNITION

XII. CYRIL'S STORY

XIII. MRS. TUNKS' DISCOVERY

XIV. WHAT SILAS PENCE KNEW

XV. DURGO, THE DETECTIVE

XVI. THE PAPERS

XVII. A CONFESSION

XVIII. THE GHOST

XIX. AN AWKWARD POSITION

XX. THE MASTER MAGICIAN

XXI. A DESPERATE ATTEMPT

XXII. MRS. VAND'S REPENTANCE

XXIII. WHAT LUKE TUNKS SAW

XXIV. A REMARKABLE DISCOVERY

XXV. RUN TO EARTH

THE SOLITARY FARM

CHAPTER I

THE DOMAIN OF CERES

"S' y' want t' merry m' gel, Bella!" remarked Captain Huxham, rubbinghis stout knees slowly, and repeating the exact words of the clericalsuitor. "S' thet she may be yer handmaiden, an' yer spouse, and yersealed fountain, es y' put it in yer flowery pulpit lingo. Jus' so! Jus'so!" and shifting the quid which bulged his weather-beaten cheek, hestared with hard blue eyes. "Jus' so, Mr. Pence!"

The young minister and the elderly skipper discussed the subject ofmarriage in a shabby antique room of small size, which had theappearance of having been used to more aristocratic company. Thedark-oak panelled walls, the grotesquely-carved ceiling-beams, theDutch-tiled fire-place, with its ungainly brass dogs, and the deepslanting embrasure of the lozenge-paned casement, suggested Georgianbeaux and belles dancing buckram minutes, or at least hard-ridingcountry squires plotting Jacobite restoration. But these happenings werein the long-ago, but this stately Essex manor-house had declinedwoefully from its high estate, and now sheltered a rough and readymariner, who camped, rather than dwelt, under its roof.

Captain Huxham, seated on the broad, low window-sill, thrust his handsinto the pockets of his brass-buttoned pea-jacket, and swung his short,sturdy legs, which were enveloped in wide blue-cloth trousers. He was asquat man, with lengthy arms and aggressively square shoulders, and hislarge, flat face was as the winter sun for redness. Clean-shaven, savefor a fringe of white hair which curved under his stubborn chin from onelarge ear to the other, his tough skin was seamed with innumerablewrinkles, accumulating particularly thickly about his eyes. He had goldrings in his ears, and plenteous grey hair hung like seaweed from undera peaked cap, pushed back from his lined forehead. He looked what hetruly was--a rough, uneducated, imperious old sea-dog, whose knowledgeof strong drink and stronger language was only exceeded by his strenuousgrip of the purse which held the savings of many rapacious years. Inthis romantic room he looked entirely out of place. Nevertheless it washis own property, and while considering his answer to Mr. Pence, heexamined it mechanically.

To the left he beheld a large open fire-place, which gaped under anornate oak mantel-piece, carved with the crest and motto of thedispossessed family. A door appeared on the right, leading to theentrance hall, and this also was elaborately carved with wreaths offruit and flowers, and with fat, foolish Cupids, entangled in knots ofribbon. The fourth wall was unbroken, and faced the window, but againstit stood a common deal table covered incongruously with an embroideredIndian cloth. Above this, and leaning forward, was a round convexmirror, surmounted by a Napoleonic eagle. This was flanked on one sideby an oilskin coat and a sou'-wester, and on the other by a sextant anda long brass telescope. A Louis Quinze sofa, with a gilt frame, andcovered with faded brocade, fitted into the space between the fire-placeand the casement. In the opposite corner, with its back to the outerwall, stood a large modern office-desk of mahogany, with a flexiblecurved lid, which was drawn down and fastened, because a visitor was inthe room. Captain Huxham never received anyone in his sanctum unless hefirst assured himself that the desk was closed, and a small,green-painted safe near it fast-locked.

There were three or four rush-bottomed chairs, which looked plebeianeven on the dusty, uncarpeted floor. On the mantel-shelf stood alyre-shaped clock, bearing the sun symbol of Louis XIV.; several cheapand gaudy vases, and many fantastic shells picked up on South Seabeaches. Here and there were Japanese curios, Polynesian mats and warweapons; uncouth Chinese idols, stuffed birds, Indian ivory carvings,photographs and paintings of various ships, and all the flotsam andjetsam which collects in a sailor's sea-chest during endless voyages.The deal table was littered with old magazines, yellow-backed novels,and navigation books with ragged covers; while the fire-place was aspecies of dust-bin for matches, cigar-ends, torn papers, orange peel,and such like. Everywhere the dust lay thick. It was an odd room--atonce sumptuous and dingy, markedly chaotic, yet orderly in an untidyway. It reflected more or less the mind of its present owner, who, ashas been before remarked, camped, rather than lived, amidst hissurroundings. In the same way do Eastern nomads house in the ruinedpalaces of kings.

Silas Pence, who was the minister of the Little Bethel Chapel inMarshely village, curled his long thin legs under his chair and lookedanxiously at his meditative host. That portion of the light from thecasement not intercepted by Huxham's bulky figure, revealed a lean,eager face, framed in sparse, fair hair, parted in the centre andfalling untidily on the coat collar. The young preacher's features weresharply defined and somewhat mean, while a short and scanty beardscarcely concealed his sensitive mouth. His forehead was lofty, his chinweak, and his grey eyes glittered in a strange, fanatical fashion. Therewere exceptional possibilities both for good and evil in that palecountenance, and it could be guessed that environment would have much todo with the development of such possibilities. Mr. Pence was arrayed ina tightly-fitting frock coat and loose trousers, both of wornbroadcloth. He wore also a low collar with a white tie, bow-fashion,white socks, and low-heeled shoes, and every part of his attire,although neat and well-brushed and well-mended, revealed dire poverty.On the whole, he had the rapt ascetic gaze of a mediaeval saint, and amonkish robe would have suited him better than his semi-ecclesiasticalgarb as a Non-conformist preacher.

But if Pence resembled a saint, Huxham might have passed for a grey oldbadger, sullen and infinitely wary. Having taken stock of his worldlypossessions, recalling meanwhile a not altogether spotless past, hebrought his shrewd eyes back again to his visitor's attentive face.Still anxious to gain time for further consideration, he remarked oncemore, "So' y' want t' merry m' gel, Bella, Mr. Pence? Jus' so! Jus' so!"

The other replied, in a musical but high-pitched voice almost femininein its timbre, "I am not comely; I am not wealthy; nor do I sit in theseat of the rulers. But the Lord has gifted me with a pleading tongue,an admiring eye, and an admonishing nature. With Isabella by my side,Brother Huxham, I can lead more hopefully our little flock towards thepleasant land of Beulah. What says Isaiah?"

"Dunno!" confessed the mari

ner. "Ain't bin readin' Isaiaher's loglately."

"Thou shalt be called Hephzibah," quoted Mr. Pence shrilly, "and thyland Beulah: for the Lord delighteth in thee, and thy land will bemarried."

"Didn't know es Isaiaher knew of m' twenty acres," growled Huxham, withanother turn of his quid; "'course ef it be, es y' merry Bella, th' landgoes with her when I fits int' m' little wooden overcoat. Y' kin takeyer davy on thet, Mr. Pence, fur I've a conscience, I hev,--let 'em saycontrary es likes."

It must have been an uneasy conscience, for Captain Huxham glareddefiantly at his visitor, and then cast a doubtful look over his leftshoulder, as though he expected to be tapped thereon. Pence was puzzledas much by this behaviour as by the literal way in which the sailor hadtaken the saying of the prophet. "Isaiah spoke in parables," heexplained, lamely.

"Maybe," grunted Huxham, "but y' speak sraight 'nough, Mr. Pence.Touching this merrage. Y' love Bella, es I take it?"

"I call her Hephzibah," burst out the young minister enthusiastically,"which, being interpreted, means--my delight is in her."

"Jus' so! Jus' so! But does th' gel love you, Mr. Pence?"

The face of the suitor clouded. "I have my doubts," he sighed, "seeingthat she has looked upon vanity in the person of a man from Babylon."

"Damn your parables!" snapped the captain; "put a blamed name t' him."

"Mr. Cyril Lister," began Pence, and was about to reprove his host forthe use of strong language, when he was startled by much worse. AndHuxham grew purple in the face when using it.

It is unnecessary to set down the exact words, but the fluency andoriginality and picturesqueness of the retired mariner's speech madeSilas close his scandalised ears. With many adjectives of the most luriddescription, the preacher understood Huxham to say that he would see hisdaughter grilling in the nethermost pit of Tophet before he would permithis daughter to marry this--adjective, double adjective--swab fromLondon.

"I ain't seen th' blighter," bellowed the captain, furiously, "but I'veheard of his blessed name. Bella met him et thet blamed Miss Ankers',the school-mistress', house, she did. Sh' wanted him t' kim an' see thisold shanty, 'cause he writes fur the noospapers, cuss him. But I up an'tole her, es I'd twist her damned neck ef she spoke agin with thelop-sided--"

"Stop! stop!" remonstrated Pence feebly. "We are all brothers in----"

"The lubber ain't no relative o' mine, hang him; an' y' too, fur sayin'so. Oh, Lister, Lister!" Huxham swung two huge fists impotently. "I hatehim."

"Why? why? why?" babbled the visitor incoherently.

The surprise in his tones brought Huxham to his calmer senses, like thecunning old badger he was.

"'Cause I jolly well do," he snorted, wiping his perspiring face with aflaunting red and yellow bandana. "But it don't matter nohow, and I arskyer pardon fur gittin' up steam. My gel don't merry no Lister, y' kinlay yer soul t' thet, Mr. Pence. Lister! Lister!" He slipped off thesill in his excitement. "I hates the whole damned breed of 'em;sea-cooks all, es oughter t' hev their silly faces in the slush tub."

"Do you know the Lister family then?" asked Pence, open-mouthed at thisvehemence.

This remark cooled the captain still further. "Shut yer silly mouth," hegrowled, rolling porpoise-fashion across the room, "and wait till I gitm' breath back int' m' bellers."

Being a discreet young man, Pence took the hint and silently watched thesquat, ungainly figure of his host lunging and plunging in the narrowconfines of the apartment. Whatever may have been the reason, it wasevident that the name of Lister acted like a red rag to this nauticalbull. Pence ran over in his mind what he knew of the young stranger, tosee if he could account for this outbreak. He could recall nothingpertinent. Cyril Lister had come to remain in Marshely some six monthspreviously, and declared himself to be a journalist in search of quiet,for the purpose of writing a novel. He occupied a tiny cottage in thevillage, and was looked after by Mrs. Block, a stout, gossiping widow,who spoke well of her master. So far as Pence knew, Captain Huxham hadnever set eyes on the stranger, and could not possibly know anything ofhim or of his family. Yet, from his late outburst of rage, it wasapparent that he hated the young man.

Lister sometimes went to London, but for the most part remained in thevillage, writing his novel and making friends with the inhabitants. Atthe house of the board-school mistress he had met Bella Huxham, and thetwo had been frequently in one another's company, in spite of thecaptain's prohibition. But it was evident that Huxham knew nothing oftheir meetings. Pence did, however, and resented that the girl shouldprefer Lister's company to his own. He was very deeply in love, and itrejoiced his heart when he heard how annoyed the captain was at the mereidea of a marriage between Lister and his daughter. The preacher was byno means a selfish man, or a bad man, but being in love he naturallywished to triumph over his rival. He now knew that his suit would besupported by Huxham, if only out of his inexplicable hatred for thejournalist.

Meanwhile Huxham stamped and muttered, and wiped his broad face as hewalked off his anger. Finally he stopped opposite his visitor and wavedhim to the door. "Y' shell merry m' gel, Bella," he announced hoarsely;"m' conscience won't let me merry her t' thet--thet--oh, cuss him! whycarn't he an' the likes o' he keep away!" He paused, and again cast anuncomfortable look over his left shoulder. "Kim up on th' roof," he saidabruptly, driving Pence into the entrance hall. "I'll show y' wot I'llgive y' with m' gel--on conditions."

"Conditions!" The preacher was bewildered.

Huxham vouchsafed no reply, but mounted the shallow steps of the grandstaircase. The manor-house was large and rambling, and of great age,having been built in the reign of Henry VII. The rooms were spacious,the corridors wide, and the ceilings lofty. The present possessor ledhis guest up the stairs into a long, broad passage, with many doorsleading into various bedrooms. At the end he opened a smaller door toreveal a narrow flight of steep steps. Followed by the minister, Huxhamascended these, and the two emerged through a wooden trap-door on theroof. Silas then beheld a moderately broad space running parallel withthe passage below, and extending from one parapet to the other. Oneither side of this walk--as it might be termed--the red-tiled roofssloped abruptly upward to cover the two portions of the mansion, herejoined by the flat leads forming the walk aforesaid. On the slope of theleft roof, looking from the trap-door, was a wooden ladder which led upto a small platform, also of wood, built round the emerging chimneystack. This was Captain Huxham's quarter deck, whither he went onoccasions to survey his property. He clambered up the ladder with theagility of a sailor, in spite of his age, and was followed by thepreacher with some misgivings. These proved to be correct, for when hereached the quarter-deck, the view which met his startled eyes so shookhis nerve, that he would have fallen but that the captain propped him upagainst the broad brick-work of the chimney.

"Oh, me," moaned the unfortunate Silas, holding on tightly to the ironclamps of the brick-work. "I am throned on a dangerous eminence," andclosed his eyes.

"Open 'em, open 'em," commanded the captain gruffly, "an' jes' look etthem twenty acres of corn, es y'll git with m' gel when I'm a deader."

Pence slipped into a sitting position and looked as directed. He beheldfrom his dizzy elevation the rolling marshland, extending from thefar-distant stream of the Thames to the foot of low-lying inland hills.As it was July, and the sun shone strongly, the marshes werecomparatively dry, but here and there Pence beheld pools and ditchesflashing like jewels in the yellow radiance. Immediately before him hecould see the village of Marshely, not so very far away, with red-roofedhouses gathered closely round the grey, square tower of the church; hecould even see the tin roof of his own humble Bethel gleaming likesilver in the sunlight. And here and there, dotted indiscriminately,were lonely houses, single huts, clumps of trees, and on the higherground rising inland, more villages similar to Marshely. The flat andperilously green lands were divided by hedges and ditches and fencesinto squares and triangles and oblongs and rectangles, all asemerald-hued as faery rings. The human habi

tations were so scattered,that it looked as though some careless genii had dropped them by chancewhen flying overhead. Far away glittered the broad stream of the Thames,with ships and steamers and boats and barges moving, outward and inwardbound, on its placid surface. The rigid line of the railway shotstraightly through villages and trees and occasional cuttings, acrossthe verdant expanse, with here and there a knot representing a station.Smoke curled from the tall chimneys of the dynamite factories near theriver, and silvery puffs of steam showed that a train was on its way toTilbury. All was fresh, restful, beautiful, and so intensely green as tobe suggestive of early Spring buddings.

"When I took command of this here farm, ten years back," observedCaptain Huxham, drawing in a deep breath of moist air, "it werewater-logged like a derelict, es y' might say. Cast yer weather-eye overit now, Mr. Pence, an' wot's yer look-out: a gardin of Edin, smilin'with grain."

"Yet it's a derelict still," remarked the preacher, struggling to hisfeet and holding on by the chimney; "let me examine your farm ofBleacres."

Bleacres--a corruption of bleakacres--consisted of only twenty acres notat all bleak, but a mere slice out of the wide domains formerly owned bythe aristocratic family dispossessed by Huxham. It extended all roundthe ancient manor-house, which stood exactly in the centre, and everyfoot of it was sown with corn. On every side waved the greenish-bluishcrop, now almost breast high. It rolled right up to the walls of thehouse, so that this was drowned, so to speak, in the ocean of grain. Thevarious fields were divided and sub-divided by water-ways wide andnarrow, which drained the land, and these gave the place quite a Dutchlook, as fancy might picture them as canals. But the corn greweverywhere so thick and high, in contrast to the barren marshes, thatthe farm looked almost aggressively cultivated. Bleacres was widelyknown as "The Solitary Farm," for there was not another like it for manymiles, though why it should have been left to a retired sailor tocultivate the soil it is hard to say. But Huxham for many years had sowncorn on his twenty acres, so that the mansion for the most part of theyear was quite shut off from the world. Only a narrow path was left,which meandered from the front door and across various water-ways toMarshely village, one mile distant. In no other way save by this pathcould the mansion be approached. And as guardian of the place ared-coated scarecrow stood sentinel a stone-throw from the house. Thebit of brilliant colour looked gay amidst the rolling acres of green.

"The domain of Ceres," said Pence dreamily, and recalling his meagreclassical studies; "here the goddess might preside. Yet," he addedagain, with a side glance at his rugged host, "a derelict still."

"Mr. Pence don't know the English langwidge, apparently," said Huxham,addressing the landscape with a pitying smile. "A derelict's a shipabandoned."

"And a derelict," insisted Pence, "can also be described as a tract ofland left dry by the sea, and fit for cultivation or use. You will findthat explanation in Nuttall's Standard Dictionary, captain."

"Live an' larn; live an' larn," commented Huxham, accepting theexplanation without question; "but I ain't got no use for dix'onariesm'self. Made m' dollars to buy this here farm without sich truck."

"In what way, captain?" asked Silas absently, and looked at the view.

Had he looked instead at Huxham's weather-beaten face he might have beensurprised. The captain grew a little trifle paler under his bronze, anuneasy look crept into his hard blue eyes, and he threw another anxiousglance over his shoulder. But a stealthy examination of the minister'sindifferent countenance assured him that the question, although aleading one, had been asked in all innocence. And in all innocence thecaptain replied, for the momentary pause had given him time to frame hisreply.

"I arned m' dollars, Mr. Pence, es an honest man should, by sweatin' onth' high an' narrer seas these forty year'. Ran away fro' m' father, eswos a cobbler," added Huxham, addressing the landscape once more, "whenI wos ten year old, an' a hop-me-thumb et thet, es y' could hev squeezedint' a pint pot. Cabin boy, A.B., mate, fust an' second, and a skipperby m' own determination t' git top-hole. Likewise hard tack, coldquarters, kickin's an' brimstone langwidge es would hev made thet hairof yours curl tremenjous, Mr. Pence. I made 'nough when fifty an' more,t' buy this here farm, an' this here house, th' roof of which I'vewalked quarter-deck fashion, es y' see, these ten years--me bein' sixtyodd, so t' speak. Waitin' now fur a hail t' jine th' angels, an' Mrs.Arabeller Huxham, who is a flier with a halo, an' expectin' me aloft, esshe remarked frequent when chokin' in her engine pipes. Asthma et wos,"finished the widower, spitting out some tobacco juice, "es settled herhash."

This astonishing speech, delivered with slow gruffness, did not startleSilas, as he had known Captain Huxham for at least five years, and hadbefore remarked upon his eccentric way of talking. "Very interesting;very commendable," he murmured, and returned to the object of his visit."And your daughter, sir?"

"Y' shell hev her, an' hev this here," the captain waved his hand to thefour points of the compass, "when I jine the late Mrs. Arabeller Huxham,ef y'--ef y'--thet is----" he halted dubiously.

"If what?" demanded Pence, unsuspiciously.

"Ef y' chuck thet Lister int' one of them water-ways," said Huxham.

"What?" cried the preacher, considerably startled.

"I want him dead," growled Huxham gruffly, "drown dead an' buried."

Perhaps his sojourn in distant lands on the fringes of the empire hadfamiliarised the captain with sudden death and murder, for he made thisamazing proposition in a calm and cheerful voice. But the minister wasnot so steeled to horrors.

"What?" he repeated in a shaking voice and with dilated eyes.

"All fur you," murmured the tempter persuasively, "every blamed acre ofet, t' say nothing of Bella es is a fine gel, an'----"

"No, no, no!" cried Silas vehemently, spreading his hands across hislean, agitated face, "how dare you ask such a thing?"

"Jus' a push," went on Huxham softly, "he bein' on the edge of one ofthem ditches, es y' might say. Wot th' water gits th' water holds. He'dgo down int' the black slime an' never come up. It 'ud choke him. Cussme," murmured Huxham softly, "I'd like t' see the black slime choke aLister."

Pence gasped again and recalled how the Evil One had taken the Saviourof men up to an exceedingly high mountain, to show Him the kingdoms ofthe world and the glory of them. "All these things will I give thee,"said Satan, "if----"

"No!" shouted Silas, his eyes lighting up with wrath. "Get thee behindme----" Before finishing his sentence, and before Huxham could reply, hescrambled down the ladder to rush for the open trap. The captain leanedfrom his quarter-deck scornfully. "Y' needn't say es I gave y' thechance, fur no one 'ull believe y'," he cried out, coolly, "an' amilksop y' are. Twenty acres, a house, an' a fine gel--y'd be set up forlife, ef y'd only push----"

Pence heard no more. In a frenzy of horror he dropped through thetrap-door, inwardly praying that he might be kept from temptation.Huxham saw him vanish and scowled. "Blamed milky swab," he grumbled,then turned to survey the bribe he had offered for wilful murder. Helooked at the corn and across the corn uneasily, as though he saw dangerin the distance. "No cause to be afeared," muttered the ex-mariner; "hecan't get through the corn. It keeps me safe anyhow."

But who the "he" referred to might be, Huxham did not say.

The Crowned Skull

The Crowned Skull Madame Midas

Madame Midas The Opal Serpent

The Opal Serpent The Solitary Farm

The Solitary Farm The Mystery Queen

The Mystery Queen The Bishop's Secret

The Bishop's Secret Red Money

Red Money The Red Window

The Red Window The Pagan's Cup

The Pagan's Cup The Third Volume

The Third Volume A Coin of Edward VII: A Detective Story

A Coin of Edward VII: A Detective Story Hagar of the Pawn-Shop

Hagar of the Pawn-Shop The Millionaire Mystery

The Millionaire Mystery The Mystery of a Hansom Cab

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab