- Home

- Fergus Hume

The Opal Serpent Page 25

The Opal Serpent Read online

Page 25

CHAPTER XXV

A CRUEL WOMAN

"Jus' say your meanin', my pretty queen," said Mrs. Tawsey, as she stoodat the sitting-room door, and watched Sylvia reading an ill-writtenletter. "It's twelve now, and I kin be back by five, arter a long, andenjiable tork with Matilder."

"You certainly must go," replied Sylvia, handing back the letter. "I amsure your sister will be glad to see you, Debby."

Deborah sniffed and scratched her elbow. "Relatives ain't friends in ourfamily," she said, shaking her head, "whatever you may say, mydeary-sweet. Father knocked mother int' lunatics arter she'd nagged 'imto drunk an' police-cells. Three brothers I 'ad, and all of 'em that'andy with their fistises as they couldn't a-bear to live in 'armonywithout black eyes and swolled bumps all over them. As to Matilder, shean' me never did, what you might call, hit it orf, by reason of 'er notgivin' way to me, as she should ha' done, me bein' the youngest and whatyou might call the baby of the lot. We ain't seen each other fur years,and the meetin' will be cold. She'll not have much forgiveness fur mebein' a bride, when she's but a lone cross-patch, drat her."

"Don't quarrel with her, Debby. She has written you a very nice letter,asking you to go down to Mrs. Krill's house in Kensington, and shereally wants to see you before she goes back to Christchurch to-night."

"Well, I'll go," said Deborah, suddenly; "but I don't like leavin' youall by your own very self, my sunflower."

"I'll be all right, Debby. Paul comes at four o'clock, and you'll beback at five."

"Sooner, if me an' Matilder don't hit if orf, or if we hit each other,which, knowin' 'er 'abits, I do expects. But Bart's out till six, andthere won't be anyone to look arter them as washes--four of 'em," addedMrs. Tawsey, rubbing her nose, "and as idle as porkpines."

"Mrs. Purr can look after them."

"Look arter gin more like," said Deborah, contemptuously. "She's allayssuckin', sly-like, tryin' to purtend as it's water, as if the smelldidn't give it away, whatever the color may be. An' here she is, idlingas usual. An' may I arsk, Mrs. Purr ma'am," demanded Deborah with greatpoliteness, "wot I pays you fur in the way of ironin'?"

But Mrs. Purr was too excited to reply. She brushed past her indignantmistress and faced Sylvia, waving a dirty piece of paper. "Lor', miss,"she almost screamed, "you do say as you want t'know where that limb Tray'ave got to--"

"Yes--yes," said Sylvia, rising, "he escaped from Mr. Hurd, and we wantto find him very much."

"It's a letter from 'im," said Mrs. Purr, thrusting the paper intoSylvia's hand; "tho' 'ow he writes, not 'avin' bin to a board school, Idunno. He's in a ken at Lambith, and ill at that. Want's me t'go an' see'im. But I can't leave the ironin'."

"Yuss y' can," said Deborah, suddenly; "this erringd is ness'ary, Mrs.Purr ma'am, so jes' put on your bunnet, an' go to Mr. Hurd as 'as 'isorfice at Scotlan' Yard, and take 'im with you."

"Oh! but I couldn't--"

"You go," advised Mrs. Tawsey. "There's five pounds offered for thebrat's bein' found."

"Five pun!" gasped Mrs. Purr, trembling. "Lor', and me 'avin' a chanctof gittin' it. I'll go--I'll go. I knows the Yard, 'avin' 'ad summat todo with them dirty perlice in my time. Miss Sylvia--"

"Yes, go, Mrs. Purr, and see Mr. Hurd. He'll give you the five pounds ifyou take him to Tray." Sylvia handed back the paper. "Tray seems to beill."

"Ill or well, he sha'n't lose me five pun, if I 'ave to drag 'im to thelock-up m'self," said Mrs. Purr, resolutely. "Where's my bunnet--myshawl--oh lor'--five pun! Them is as good allays gits rewards," and shehurried out, hardly able to walk for excitement.

"There's a nice ole party fur you, Miss Sylvia?"

"Debby," said the girl, thoughtfully. "You take her to the Yard to seeMr. Hurd, and then go to Kensington to speak with your sister."

"Well, I'll go, as importance it is," said Mrs. Tawsey, rubbing her noseharder than ever. "But I 'opes you won't be lone, my poppet-dovey."

"Oh, no," said Sylvia, kissing her, and pushing her towards the door."I'll look after those four women in the wash-house, and read this newbook I have. Then I must get tea ready for Paul, who comes at four. Theafternoon will pass quite quickly."

"I'll be back at five if I can, and earlier if Matilder ain't what sheoughter be," said Mrs. Tawsey, yielding. "So make yourself 'appy, honey,till you sees me smilin' again."

In another quarter of an hour Mrs. Tawsey, dressed in her bridal gownand bonnet so as to crush Matilda with the sight of her splendor, walkeddown the garden path attended by Mrs. Purr in a snuffy black shawl, anda kind of cobweb on her head which she called a "bunnet." As Deborah wastall and in white and Mrs. Purr small and in black, they looked astrange pair. Sylvia waved her hand out of the window to Debby, as thatfaithful creature turned her head for a final look at the young mistressshe idolized. The large, rough woman was dog-like in her fidelity.

Sylvia, left alone, proceeded to arrange matters. She went to thewash-house, which was detached from the cottage, and saw that the fourwomen, who worked under Deborah, were busy. She found them allchattering and washing in a cheerful way, so, after a word or two ofcommendation, she returned to the sitting-room. Here she played a gameof patience, arranged the tea-things although it was yet early, andfinally settled down to one of Mrs. Henry Wood's interesting novels. Shewas quite alone and enjoyed the solitude. The wash-house was so faraway, at the end of the yard, that the loud voices of the workers couldnot be heard. The road before Rose Cottage was not a popularthoroughfare, and it was rarely that anyone passed. Out of the windowSylvia could see a line of raw, red-brick villas, and sometimes a spurtof steam, denoting the presence of the railway station. Also, she sawthe green fields and the sere hedges with the red berries, givingpromise of a hard winter. The day was sunny but cold, and there was afeeling of autumnal dampness in the air. Deborah had lighted a firebefore she went, that her mistress might be comfortable, so Sylvia satdown before this and read for an hour, frequently stopping to think ofPaul, and wonder if he would come at the appointed hour of four orearlier. What with the warmth, and the reading, and the dreaming, shefell into a kind of doze, from which she was awakened by a sharp andperemptory knock. Wondering if her lover had unexpectedly arrived,though she did not think he would rap in so decided a manner, Sylviarubbed the sleep out of her pretty eyes and hurried to the door. On thestep she came face to face with Miss Maud Krill.

"Do you know me, Miss Norman?" asked Maud, who was smiling and suave,though rather white in the face.

"Yes. You came with your mother to Gwynne Street," replied Sylvia,wondering why she had been honored with a visit.

"Quite so. May I have a few minutes' conversation with you?"

"Certainly." Sylvia saw no reason to deny this request, although she didnot like Miss Krill. But it struck her that something might be learnedfrom that young woman relative to the murder, and thought she would havesomething to tell Paul about when he arrived. "Will you walk in,please," and she threw open the sitting-room door.

"Are you quite alone?" asked Maud, entering, and seating herself in thechair near the fire.

"Quite," answered Sylvia, stiffly, and wondering why the question wasasked; "that is, the four washerwomen are in the place at the back. ButMrs. Tawsey went to your house to see her sister."

"She arrived before I left," said Maud, coolly. "I saw them quarrellingin a most friendly way. Where is Mr. Beecot?"

"I expect him later."

"And Bart Tawsey who married your nurse?"

"He is absent on his rounds. May I ask why you question me in this way,Miss Krill?" asked Sylvia, coldly.

"Because I have much to say to you which no one else must hear," was thecalm reply. "Dear me, how hot this fire is!" and she moved her chair sothat it blocked Sylvia's way to the door. Also, Miss Krill cast a glanceat the window. It was not snibbed, and she made a movement as if to goto it; but, restraining herself, she turned her calm, cold face to thegirl. "I have much to say to you," she repeated.

"Indeed," replied Sylvia, politely, "I don

't think you have treated meso well that you should trouble to converse with me. Will you please tobe brief. Mr. Beecot is coming at four, and he will not be at allpleased to see you."

Maud glanced at the clock. "We have an hour," she said coldly; "it isjust a few minutes after three. My business will not take long," sheadded, with an unpleasant smile.

"What is your business?" asked Sylvia, uneasily, for she did not likethe smile.

"If you will sit down, I'll tell you."

Miss Norman took a chair near the wall, and as far from her visitor aswas possible in so small a room. Maud took from her neck a black silkhandkerchief which she wore, evidently as a protection against the cold,and folding it lengthways, laid it across her lap. Then she looked atSylvia, in a cold, critical way. "You are very pretty, my dear," shesaid insolently.

"Did you come to tell me that?" asked the girl, firing up at the tone.

"No. I came to tell you that my mother was arrested last night for themurder of _our_ father."

"Oh," Sylvia gasped and lay back on her chair, "she killed him, thatcruel woman."

"She did not," cried Maud, passionately, "my mother is perfectlyinnocent. That blackguard Hurd arrested her wrongfully. I overheard allthe conversation he had with her, and know that he told a pack of lies.My mother did _not_ kill our father."

"My father, not yours," said Sylvia, firmly.

"How dare you. Lemuel Krill was my father."

"No," insisted Sylvia. "I don't know who your father was. But from yourage, I know that you are not--"

"Leave my age alone," cried the other sharply, and with an uneasymovement of her hands; "we won't discuss that, or the question of myfather. We have more interesting things to talk about."

"I won't talk to you at all," said Sylvia, rising.

"Sit down and listen. You _shall_ hear me. I am not going to let mymother suffer for a deed she never committed, nor am I going to let youhave the money."

"It is mine."

"It is not, and you shall not get it."

"Paul--Mr. Beecot will assert my rights."

"Will he indeed," said the other, with a glance at the clock; "we'll seeabout that. There's no time to be lost. I have much to say--"

"Nothing that can interest me."

"Oh, yes. I think you will find our conversation very interesting. I amgoing to be open with you, for what I tell you will never be told by youto any living soul."

"If I see fit it shall," cried Sylvia in a rage; "how dare you dictateto me."

"Because I am driven into a corner. I wish to save my mother--how it isto be done I don't know. And I wish to stop you getting the fivethousand a year. I know how _that_ is to be done," ended Miss Krill,with a cruel smile and a flash of her white, hungry-looking teeth; "yourat of a girl--"

"Leave the room."

"When I please, not before. You listen to me. I'm going to tell youabout the murder--"

"Oh," said Sylvia, turning pale, "what do you mean?"

"Listen," said the other, with a taunting laugh, "you'll be white enoughbefore I've done with you. Do you see this," and she laid her finger onher lips; "do you see this scar? Krill did that." Sylvia noticed thatshe did not speak of Krill as her father this time; "he pinned my lipstogether when I was a child with that opal serpent."

"I know," replied Sylvia, shuddering, "it was cruel. I heard about itfrom the detective and--"

"I don't wish for your sympathy. I was a girl of fifteen when that wasdone, and I will carry the scar to my grave. Child as I was then, Ivowed revenge--"

"On your father," said Sylvia, contemptuously.

"Krill is not my father," said Maud, changing front all at once; "he isyours, but not mine. My father is Captain Jessop. I have known this foryears. Captain Jessop told me I was his daughter. My mother thought thatmy father was drowned at sea, and so married Krill, who was a travellerin jewellery. He and my mother rented 'The Red Pig' at Christchurch, andfor years they led an unhappy life."

"Oh," gasped Sylvia, "you confess. I'll tell Paul."

"You'll tell no one," retorted the other woman sharply. "Do you think Iwould speak so openly in order that you might tell all the world withyour gabbling tongue? Yes, and I'll speak more openly still before Ileave. Lady Rachel Sandal did not commit suicide as my mother said. Shewas strangled, and by me."

Sylvia clapped her hands to her face with a scream. "By you?"

"Yes. She had a beautiful brooch. I wanted it. I was put to bed by mymother, and kept thinking of the brooch. My mother was down the stairsattending to your drunken father. I stole to Lady Rachel's room andfound her asleep. I tried to take the brooch from her breast. She wokeand caught at my hand. But I tore away the brooch and before Lady Rachelcould scream, I twisted the silk handkerchief she wore, which wasalready round her throat, tighter. I am strong--I was always strong,even as a girl of fifteen. She was weak from exhaustion, so she soondied. My mother came into the room and saw what I had done. She wasterrified, and made me go back to bed. Then she tied Lady Rachel by thesilk handkerchief to the bedpost, so that it might be thought she hadcommitted suicide. My mother then came back to me and took the brooch,telling me I might be hanged, if it was found on me. I was afraid, beingonly a girl, and gave up the brooch. Then Captain Jessop raised thealarm. I and my mother went downstairs, and my mother dropped the broochon the floor, so that it might be supposed Lady Rachel had lost itthere. Captain Jessop ran out. I wanted to give the alarm, and tell theneighbors that Krill had done it--for I knew then he was not my father,and I saw, moreover, how unhappy he made my mother. He caught me," saidMaud, with a fierce look, "and bound a handkerchief across my mouth. Igot free and screamed. Then he bound me hand and foot, and pinned mylips together with the brooch which he picked off the floor. My motherfought for me, but he knocked her down. Then he fled, and after a longtime Jessop came in. He removed the brooch from my mouth and unbound me.I was put to bed, and Jessop revived my mother. Then came the inquest,and it was thought that Lady Rachel had committed suicide. But she didnot," cried Maud, exultingly, and with a cruel light in her eyes, "Ikilled her--I--"

"Oh," moaned Sylvia, backing against the wall with widely open eyes;"don't tell me more--what horrors!"

"Bah, you kitten," sneered Maud, contemptuously, "I have not half doneyet. You have yet to hear how I killed Krill."

Sylvia shrieked, and sank back in her chair, staring with horrified eyesat the cruel face before her.

"Yes," cried Maud, exultingly, "I killed him. My mother suspected me,but she never knew for certain. Listen. When Hay told me that Krill washiding as Norman in Gwynne Street I determined to punish him for hiscruelty to me. I did not say this, but I made Hay promise to get me thebrooch from Beecot--on no other condition would I marry him. I wantedthe brooch to pin Krill's lips together as he had pinned mine, when Iwas a helpless child. But your fool of a lover would not part with thebrooch. Tray, the boy, took it from Beecot's pocket when he met withthat accident--"

"How do you know Tray?"

"Because I met him at Pash's office several times when I was up. He ranerrands for Pash before he became regularly employed. I saw that Traywas a devil, of whom I could make use. Oh, I know Tray, and I know alsoHokar the Indian, who placed the sugar on the counter. He went to theshop to kill your father at my request. I wanted revenge and the money.Hokar was saved from starvation by my good mother. He came of the raceof Thugs, if you know anything about them--"

"Oh," moaned Sylvia, covering her face again.

"Ah, you do. So much the better. It will save my explaining, as there isnot much time left before your fool arrives. Hokar saw that I loved tohurt living creatures, and he taught me how to strangle cats and dogsand things. No one knew but Hokar that I killed them, and it was thoughthe ate them. But he didn't. I strangled them because I loved to see themsuffer, and because I wished to learn how to strangle in the way theThugs did."

Sylvia was sick with fear and disgust. "For God's sake, don't tell meany more," she said imploringly.

/> But she might as well have spoken to a granite rock. "You shall heareverything," said Maud, relentlessly. "I asked Hokar to strangle Krill.He went to the shop, but, when he saw that Krill had only one eye, hecould not offer him to the goddess Bhowanee. He came to me at Judson'shotel, after he left the sugar on the counter, and told me the goddesswould not accept the offering of a maimed man. I did not know what todo. I went with my mother to Pash's office, when she was arranging toprosecute Krill for bigamy. I met Tray there. He told me he had giventhe brooch to Pash, and that it was in the inner office. My mother wastalking to Pash within and I chatted to Tray outside. I told Tray Iwanted to kill Krill, and that if he would help me, I would give him alot of money. He agreed, for he was a boy such as I was when a girl,fond of seeing things suffer. You can't wonder at it in me," went onMiss Krill, coolly; "my grandmother was hanged for poisoning mygrandfather, and I expect I inherit the love of murder from her--"

"I won't listen," cried Sylvia, shuddering.

"Oh, yes, you will. I'll soon be done," went on her persecutor, cruelly."Well, then, when I found Tray was like myself I determined to get thebrooch and hurt Krill--hurt him as he hurt me," she cried vehemently."Tray told me of the cellar and of the side passage. When my mother andPash came out of the inner office and went to the door, I ran in andtook the brooch. It was hidden under some papers and had escaped mymother's eye. But I searched till I got it. Then I made an appointmentwith Tray for eleven o'clock at the corner of Gwynne Street. I went backto Judson's hotel, and my mother and I went to the theatre. We hadsupper and retired to bed. That is, my mother did. We had left thetheatre early, as my mother had a headache, and I had plenty of time.Mother fell asleep almost immediately. I went downstairs veiled, and indark clothes. I slipped past the night porter and met Tray. We went bythe side passage to the cellar. Thinking we were customers Krill let usin. Tray locked the door, and I threw myself on Krill. He had not beendrinking much or I might not have mastered him. As it was, he was tooterrified when he recognized me to struggle. In fact he fainted. WithTray's assistance I bound his hands behind his back, and then we enjoyedourselves," she rubbed her hands together, looking more like a fiendthan a woman.

Sylvia rose and staggered to the door. "No more--no more."

Maud pushed her back into her chair. "Stop where you are, you whimperingfool!" she snarled exultingly, "I have you safe." Then she continuedquickly and with another glance at the clock, the long hand of which nowpointed to a quarter to four, "with Tray's assistance I carried Krill upto the shop. Tray found an auger and bored a hole in the floor. Then Ipicked up a coil of copper wire, which was being used in packing thingsfor Krill to make his escape. I took it up. We laid Krill's neck overthe hole, and passed the wire round his neck and through the hole. Traywent down and tied a cross stick on the end of the wire, so that hecould put his weight on it when we strangled--"

"Oh--great heaven," moaned Sylvia, stopping her ears.

Maud bent over her and pulled her hands away. "You _shall_ hear youlittle beast," she snarled. "All the time Krill was sensible. Herecovered his senses after he was bound. I prolonged his agony as muchas possible. When Tray went down to see after the wire, I knelt besideKrill and told him that I knew I was not his daughter, that I intendedto strangle him as I had strangled Lady Rachel. He shrieked with horror.That was the cry you heard, you cat, and which brought you downstairs. Inever expected that," cried Maud, clapping her hands; "that was a treatfor Krill I never intended. I stopped his crying any more for assistanceby pinning his mouth together, as he had done mine over twenty yearsbefore. Then I sat beside him and taunted him. I heard the policemanpass, and the church clock strike the quarter. Then I heard footsteps,and guessed you were coming. It occurred to me to give you a treat bystrangling the man before your eyes, and punish him more severely, sincethe brooch stopped him calling out--as it stopped me--me," she cried,striking her breast.

"Oh, how could you--how could--"

"You feeble thing," said Maud, contemptuously, and patting the girl'scheek, "you would not have done it I know. But I loved it--I loved it!That was living indeed. I went down to the cellar and fastened the doorbehind me. Tray was already pressing on the cross stick at the end ofthe wire, and laughed as he pressed. But I stopped him. I heard you andthat woman enter the shop, and heard what you said. I prolonged Krill'sagony, and then I pressed the wire down myself for such a time as Ithought it would take to squeeze the life out of the beast. Then withTray I locked the cellar door and left by the side passage. We dodgedall the police and got into the Strand. I did not return to the hotel,but walked about with Tray all the night talking with--joy," cried Maud,clapping her hands, "with joy, do you hear. When it was eight I went toJudson's. The porter thought I had been out for an early walk. Mymother--"

Here Maud broke off, for Sylvia, who was staring over her shoulder outof the window saw a form she knew well at the gate. "Paul--Paul," sheshrieked, "come--come!"

Maud whipped the black silk handkerchief round the girl's neck. "Youshall never get that money," she whispered cruelly, "you shall nevertell anyone what I have told you. Now I'll show you how Hokar taughtme," she jerked the handkerchief tight. But Sylvia got her hand underthe cruel bandage and shrieked aloud in despair. At once she heard ananswering shriek. It was the voice of Deborah.

Maud darted to the door and locked it. Then she returned and, flingingSylvia down, tried again to tighten the handkerchief, her face white andfierce and her eyes glittering like a demon's.

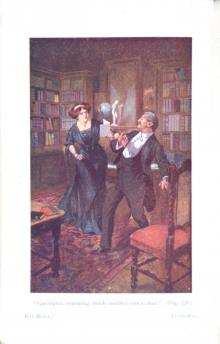

"Help--help!" cried Sylvia, and her voice grew weaker. But she struggledand kept her hands between the handkerchief and her throat. Maud triedto drag them away fiercely. Deborah was battering frantically at thedoor. Paul ran round to the window. It was not locked, and Maud,struggling with Sylvia had no time to close it. With a cry of alarm Paulthrew up the window and jumped into the room. At the same momentDeborah, putting her sturdy shoulder to the frail door, burst it open.Beecot flung himself on the woman and dragged her back. But she clunglike a leech to Sylvia with the black handkerchief in her grip. Deborah,silent and fierce, grabbed at the handkerchief, and tore it from Maud'sgrasp. Sylvia, half-strangled, fell back in a faint, white as a corpse,while Paul struggled with the savage and baffled woman.

"You've killed her," shouted Deborah, and laid her strong hands on Maud,"you devil!" She shook her fiercely. "I'll kill you," and she shook heragain.

Paul threw himself on his knees beside the insensible form of Sylvia andleft Deborah to deal with Maud. That creature was gasping as Mrs. Tawseyswung her to and fro. Then she began to fight, and the two women crashedround the little room, upsetting the furniture. Paul took Sylvia in hisarms, and shrank against the wall to protect her.

A new person suddenly appeared. No less a woman than Matilda. When shesaw Maud in Deborah's grip she flew at her sister like a tigress anddragged her off. Maud was free for a moment. Seeing her chance shescrambled out of the window, and ran through the garden down the roadtowards the station. Perhaps she had a vague idea of escape. Deborah,exerting her great strength, threw Matilda aside, and without a cry ranout of the house and after the assassin who had tried to strangleSylvia. Matilda, true to her salt, ran also, to help Maud Krill, and thetwo women sped in the wake of the insane creature who was swiftlyrunning in the direction of the station. People began to look round, acrowd gathered like magic, and in a few moments Maud was being chased byquite a mob of people. She ran like a hare. Heaven only knows if shehoped to escape after her failure to kill Sylvia, but she ran onblindly. Into the new street of Jubileetown she sped with the roaringmob at her heels. She darted down a side thoroughfare, but Deborahgained on her silently and with a savage look in her eyes. Severalpolicemen joined in the chase, though no one knew what the flying womanhad done. Maud turned suddenly up the slope that led to the station. Shegained the door, darted through it, upset the man at the barrier andwith clenched fists stood at bay, her back to the rails. Deborah dartedforward--Maud gave a wild scream and sprang aside: then she reeled andfell

over the platform. The next moment a train came slowing into thestation, and immediately the wretched woman was under the cruel wheels.When she was picked up she was dead and almost cut to pieces. LadyRachel and Lemuel Krill were revenged.

CHAPTER XXVI

A FINAL EXPLANATION

Sylvia was ill for a long time after that terrible hour. Although Maudhad not succeeded in strangling her, yet the black silk handkerchiefleft marks on her neck. Then the struggle, the shock and the remembranceof the horrors related by the miserable woman, threw her into a nervousfever, and it was many weeks before she recovered sufficiently to enjoylife. Deborah never forgave herself for having left Sylvia alone, andnursed her with a fierce tenderness which was the result of remorse.

"If that wretch 'ad killed my pretty," she said to Paul, "I'd ha' killedher, if I wos hanged fur it five times over."

"God has punished the woman," said Paul, solemnly. "And a terrible deathshe met with, being mutilated by the wheels of the train."

"Serve 'er right," rejoined Deborah, heartlessly. "What kin you expectfur good folk if wicked ones, as go strangulating people, don't git theLord down on 'em. Oh, Mr. Beecot," Deborah broke down into noisy tears,"the 'orrors that my lovely one 'ave tole me. I tried to stop her, butshe would tork, and was what you might call delirous-like. Sich murdersand gory assassins as wos never 'eard of."

"I gathered something of this from what Sylvia let drop when we cameback from the station," said Beecot, anxiously. "Tell me exactly whatshe said, Deborah."

"Why that thing as is dead, an' may she rest in a peace, she don'tdeserve, tole 'ow she murdered Lady Rachel Sandal an' my ole master."

"Deborah," cried Beecot, amazed. "You must be mistaken."

"No, I ain't, sir. That thing guv my lily-queen the 'orrors. Jes you'ear, Mr. Beecot, and creeps will go up your back. Lor' 'ave mercy on usas don't know the wickedness of the world."

"I think we have learned something of it lately, Mrs. Tawsey," wasPaul's grim reply. "But tell me--"

"Wot my pore angel sunbeam said? I will, and if it gives you nightmaresdon't blame me," and Mrs. Tawsey, in her own vigorous, ungrammaticalway, related what she had heard from Sylvia. Paul was struck with horrorand wanted to see Sylvia. But this Deborah would not allow. "She'ssleepin' like a pretty daisy," said Mrs. Tawsey, "so don't you goa-disturbin' of her nohow, though acrost my corp you may make a try, saywhat you like."

But Paul thought better of it, thinking Sylvia had best be left in therough, kindly hands of her old nurse. He went off to find Hurd, andrelated all that had taken place. The detective was equally horrifiedalong with Beecot when he heard of Sylvia's danger, and set to work toprove the truth of what Maud had told the girl. He succeeded so wellthat within a comparatively short space of time, the whole matter wasmade clear. Mrs. Jessop, _alias_ Mrs. Krill, was examined, Tray wasfound and questioned, Matilda was made to speak out, and both Jessop andHokar had to make clean breasts of it. The evidence thus procured provedthe truth of the terrible confession made by Maud Jessop to the girl shethought to strangle. Hurd was amazed at the revelation.

"Never call me a detective again," he said to Paul. "For I am an ass. Ithought Jessop might be guilty, or that Hokar might have done it. Icould have taken my Bible oath that Mrs. Krill strangled the man; but Inever for one moment suspected that smiling young woman."

"Oh," Paul shrugged his shoulders, "she was mad."

"She must have been," ruminated the detective, "else she wouldn't havegiven herself away so completely. Whatever made her tell Miss Normanwhat she had done?"

"Because she never thought that Sylvia would live to tell anyone else.That was why she spoke, and thought to torture Sylvia--as she did--inthe same way as she tortured that wretched man Lemuel. If I hadn't comeearlier to Rose Cottage than usual, and if Deborah had not met meunexpectedly at the station, Sylvia would certainly have been killed.And then Maud might have escaped. She laid her plans well. It was shewho induced Matilda to get her sister to come to Kensington for a chat."

"But Matilda didn't know what Maud was up to?"

"No. Matilda never guessed that Maud was guilty of two murders ordesigned to strangle Sylvia. But Maud made use of her to get Deborah outof the house, and it was Maud who made Tray send the letter asking Mrs.Purr to come to him, so that she also might be out of the way. In factMaud arranged so that everyone should be away and Sylvia alone. If shehadn't wasted time in telling her fearful story, she might have killedmy poor love. Sylvia was quite exhausted with the struggle."

"Well," said Hurd. "I went with the old woman to the address given inthat letter which Tray got written for him. He wasn't there, however, soI might have guessed it was a do."

"But you have caught him?"

"Yes, in Hunter Street. He was loafing about there at night waiting forMaud, and quite ignorant of her death. I made him tell me everything ofhis connection with the matter. He's as bad a lot as that girl, but shehad some excuse, seeing her grandmother was a murderess; Tray is nothingbut a wicked little imp."

"Will he be hanged?"

"No, I think not. His youth will be in his favor, though I'd hang himmyself had I the chance, and so put him beyond the reach of hurtinganyone. But I expect he'll get a long sentence."

"And Mrs. Krill?"

"Mrs. Jessop you mean. Hum! I don't know. She apparently was ignorantthat Maud killed Krill, though she might have guessed it, after the wayin which Lady Rachel was murdered. I daresay she'll get off. I'm goingto see her shortly and tell her of the terrible death of her daughter."

Paul did not pursue the conversation. He was sick with the horror of thebusiness, and, moreover, was too anxious about Sylvia's health to takemuch interest in the winding up of the case. That he left in the handsof Hurd, and assured him that the thousand pounds reward, which Mrs.Krill had offered, would be paid to him by Miss Norman.

Of course, Pash had known for some time that Maud was too old to havebeen born of Mrs. Jessop's second marriage with Krill; but he never knewthat the widow had committed bigamy. He counted on keeping her under histhumb by threatening to prove that Maud was not legally entitled to themoney. But when the discovery was made at Beechill and Stowley Churchesby Miss Qian, the monkey-faced lawyer could do nothing. Beecot couldhave exposed him, and for his malpractices have got him struck off therolls; but he simply punished him by taking away Sylvia's business andgiving it to Ford. That enterprising young solicitor speedily placedthe monetary affairs on a proper basis and saw that Sylvia was properlyreinstated in her rights. Seeing that she was the only child and legalheiress of Krill, this was not difficult. The two women who hadillegally secured possession of the money had spent a great deal in avery wasteful manner, but the dead man's investments were so excellentand judicious that Sylvia lost comparatively little, and becamepossessed of nearly five thousand a year, with a prospect of her incomeincreasing. But she was too ill to appreciate this good fortune. Thecase got into the papers, and everyone was astonished at the strangesequel to the Gwynne Street mystery. Beecot senior, reading the papers,learned that Sylvia was once more an heiress, and forthwith held out anolive branch to Paul. Moreover, the frantic old gentleman, as Deborahcalled him, really began to feel his years, and to feel also that he hadtreated his only son rather harshly. So he magnanimously offered toforgive Paul on no conditions whatsoever. For the sake of his mother,the young man buried the past and went down to be received in a statelymanner by his father, and with joyful tears by his mother. Also he wasmost anxious to hear details of the case which had not been made public.Paul told him everything, and Beecot senior snorted with rage. Therecital proved too much for Mrs. Beecot, who retired as usual to bed andfortified herself with sal volatile; but Paul and his respected parentsat up till late discussing the matter.

"And now, sir," said Beecot senior, grasping the stem of his wine glass,as though he intended to hurl it at his son, "let us gather up thethreads of this infamous case. This atrocious woman who tried tostrangle your future wife?"

"She has

been buried quietly. Her mother was at the funeral and so wasthe father."

"A pretty pair," gobbled the turkey-cock, growing red. "I suppose theGovernment will hang the pair?"

"No. Captain Jessop can't be touched as he had nothing to do with themurder, and Sylvia and myself are not going to prosecute him for hisattempt to get the jewels from Pash."

"Then you ought to. It's a duty you owe to society."

Paul shook his head. "I think it best to leave things as they are,father," he said mildly, "especially as Mrs. Jessop, much broken inhealth because of her daughter's terrible end, has gone back with herhusband to live at his house in Stowley."

"What," shouted Beecot senior, "is that she-devil to go free, too?"

"I don't think she was so bad as we thought," said Paul. "I fancied shewas a thoroughly bad woman, but she really was not. She certainlycommitted bigamy, but then she thought Jessop was drowned. When he cameto life she preferred to live with Krill, as he had more money thanJessop."

"And, therefore, Jessop, as you say, had free quarters at 'The Red Pig.'A most immoral woman, sir--most immoral. She ought to be ducked."

"Poor wretch," said Paul, "her mind has nearly given way under the shockof her daughter's death. She loved that child and shielded her from theconsequences of killing Lady Rachel. The Sandal family don't want thecase revived, especially as Maud is dead, so Mrs. Jessop--as she isnow--can end her days in peace. The Government decided to let her gounder the circumstances."

"Tush," said Beecot senior, "sugar-coated pills and idiocy. Nothing willever be done properly until this Government goes out. And it will,"striking the table with his fist, "if I have anything to do with thematter. So Mrs. Krill or Jessop is free to murder, and--"

"She murdered no one," interposed Paul, quickly; "she knew that herdaughter had killed Lady Rachel, and shielded her. But she was neversure if Maud had strangled Krill, as she feared to ask her. But as thegirl was out all night at the time of the murder, Mrs. Jessop, I think,knows more than she choses to admit. However, the Treasury won'tprosecute her, and her mind is now weak. Let the poor creature end herdays with Jessop, father. Is there anything else you wish to know?"

"That boy Tray?"

"He was tried for being an accessory before the crime, but his counselput forward the plea of his age, and that he had been under theinfluence of Maud. He has been sent to a reformatory for a good numberof years. He may improve."

"Huh!" grunted the old gentleman, "and silk purses may be made out ofsow's ears; but not in our time, my boy. We'll hear more of thatjuvenile scoundrel yet. Now that, that blackguard, Hay?"

"He has gone abroad, and is likely to remain abroad. Sandal and Tempestkept their word, but I think Hurd put it about that Hay was a cheat anda scoundrel. Poor Hay," sighed Paul, "he has ruined his career."

"Bah! he never had one. If you pity scoundrels, Paul, what are you tothink of good people?"

"Such as Deborah who is nursing my darling? I think she's the best womanin the world."

"Except your mother?"

Paul nearly fell from his seat on hearing this remark. Beecot seniorcertainly might have been in earnest, but his good opinion did notprevent him still continuing to worry Mrs. Beecot, which he did to theend of her life.

"I suppose that Matilda Junk creature had nothing to do with themurder?" asked Beecot, after an embarrassing pause--on his son's part.

"No. She knew absolutely nothing, and only attacked Deborah because shefancied Deborah was attacking Maud. However, the two sisters have madeit up, and Matilda has gone back to 'The Red Pig.' She's as decent acreature as Deborah, in another way, and was absolutely ignorant ofMaud's wickedness. Hurd guessed that when she spoke to him so freely atChristchurch."

"And the Thug?"

"Hokar? Oh, he is not really a Thug, but the descendant of one. However,they can't prove that he strangled anything beyond a few cats and dogswhen he showed Maud how to use the roomal--that's the handkerchief withwhich the Thugs strangled their victims."

"I'm not absolutely ignorant," growled his father. "I know that. So thisHokar goes free?"

"Yes. He would not strangle Aaron Norman because he had but one eye, andBhowanee won't accept maimed persons. Failing him, Maud had to attend tothe job herself, with the assistance of Tray."

"And this detective?"

"Oh, Ford, with Sylvia's sanction, has paid him the thousand pounds,which he shares with his sister, Aurora Qian. But for her searching atStowley and Beechill, we should never have known about the marriage, youknow."

"No, I don't know. They're far too highly paid. The marriage would havecome to light in another way. However, waste your own money if you like;it isn't mine."

"Nor mine either, father," said Paul, sharply. "Sylvia will keep her ownfortune. I am not a man to live on my wife. I intend to take a house intown when we are married, and then I'll still continue to write."

"Without the spur of poverty you'll never make a hit," grinned the oldgentleman. "However, you can live where you please. It's no business ofmine but I demand, as your indulgent father, that you'll bring Sylviadown here at least three times a year. Whenever she is well I want tosee her."

"I'll bring her next week," said Paul, thinking of his mother. "ButDeborah must come too. She won't leave Sylvia."

"The house is big enough. Bring Mrs. Tawsey also--I'm rather anxious tosee her. And Sylvia will be a good companion for your mother."

So matters were arranged in this way, and when Paul returned to town hewent at once to tell Sylvia of the reconciliation. He found her, proppedup with pillows, seated by the fire, looking much better, although shewas still thin and rather haggard. Deborah hovered round her and spokein a cautious whisper, which was more annoying than a loud voice wouldhave been. Sylvia flushed with joy when she saw Paul, and flushed stillmore when she heard the good news.

"I am so glad, darling," she said, holding Paul's hand in her thin ones."I should not have liked our marriage to have kept you from yourfather."

Mrs. Tawsey snorted. "His frantic par," she said, "ah, well, when I meet'im, if he dares to say a word agin my pretty--"

"My father is quite ready to welcome her as a daughter," said Paul,quickly.

"An' no poor one either," cried Deborah, triumphantly. "Five thousand ayear, as that nice young man Mr. Ford have told us is right. Lor'! mylovely queen, you'll drive in your chariot and forget Debby."

"You foolish old thing," said the girl, fondly, "you held to me in mytroubles and you shall share in my joy."

"Allays purvidin' I don't 'ave to leave the laundry in charge of Bartan' Mrs. Purr, both bein' infants of silliness, one with gin and t'otherwith weakness of brain. It's well I made Bart promise to love, honor andobey me, Mr. Beecot, the same as you must do to my own lily flowerthere."

"No, _I_ am to love, honor and obey Paul," cried Sylvia.

"When?" he asked, taking her in his arms.

"As soon as I can stand at the altar," she replied, blushing, whereatDeborah clapped her hands.

"Weddin's an' weddin's an' weddin's agin," cried Mrs. Tawsey, "which mysister Matilder being weary of 'er spinstering 'ome 'ave made up 'ermind to marry the fust as offers. An' won't she lead 'im a danceneither--oh, no, not at all."

"Well, Deborah," said Beecot, "we have much to be thankful for, all ofus. Let us try and show our gratitude in our lives."

"Ah, well, you may say that," sighed Mrs. Tawsey, in a devout manner."Who'd ha' thought things would have turned out so 'appy-like indeed.But you go on with your billin', my lovely ones, and I'll git th'mutting broth to put color int' my pretty's cheeks," and she bustledout.

Sylvia's heart was too full to say anything. She lay in Paul's strongarms, her cheek against his. There she would remain for the rest of herlife, protected from storm and tempest. And as they sat in silence, thechimes of an ancient grandfather's clock, Deborah's chief treasure, rangout twice, thrice and again. Paul laughed softly.

"It's like wedding-bells," he whispered, and his futu

re wife sighed asigh of heart-felt joy.

THE END

THE BEST NOVELS BY FERGUS HUME

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab $1.25

The Sealed Message 1.25

The Sacred Herb 1.25

Claude Duval of Ninety-five 1.25

The Rainbow Feather 1.25

The Pagan's Cup 1.25

A Coin of Edward VII 1.25

The Yellow Holly 1.25

The Red Window 1.25

The Mandarin's Fan 1.25

The Secret Passage 1.25

The Opal Serpent 1.25

Lady Jim of Curzon Street 1.50

Transcriber's Note

In this the ASCII version, accents have been dropped.

The advert ("The Best Novels by Fergus Hume") was originally at thefront of the book, but has been moved to the end.

The following typographical corrections have been made:

(page 8) "furthur" changed to "further"(page 11) "Notebook" changed to "Note-book"(page 33) "lookout" changed to "look-out"(page 49) "eyeglass" changed to "eye-glass"(page 59) "hand-bag" changed to "handbag"(pages 71, 85) "agoin'" changed to "a-goin'"(page 71) "It" changed to "If" in "If we come to"(page 84) quotation mark added after "look--look--"(page 109) "Deborrah" changed to "Deborah"(page 111) quotation mark added before "How dare you"(page 113) "pou" changed to "you" ("before you became an heiress")(page 132) "is" changed to "it" ("that is was picked up")(page 140) "mid-night" changed to "midnight"(page 163) "schoolfellow" changed to "school-fellow"(page 173) "non-plussed" changed to "nonplussed"(page 180) "handbills" changed to "hand-bills"(page 188) "beliving" changed to "believing"(pages 203, 204) "bed-post" changed to "bedpost"(page 214) "sipte" changed to "spite"(page 211) used single quotation marks for the inscription(page 225) quotation mark added before "On no condition"(page 243) quotation mark added after "seem to win,"(page 264) quotation mark added before "for I"(page 269) quotation mark added after "certificate."(page 276) question mark added after "lawyer you are"(page 303) "pining" changed to "pinning"(page 315) "slience" changed to "silence"

The Crowned Skull

The Crowned Skull Madame Midas

Madame Midas The Opal Serpent

The Opal Serpent The Solitary Farm

The Solitary Farm The Mystery Queen

The Mystery Queen The Bishop's Secret

The Bishop's Secret Red Money

Red Money The Red Window

The Red Window The Pagan's Cup

The Pagan's Cup The Third Volume

The Third Volume A Coin of Edward VII: A Detective Story

A Coin of Edward VII: A Detective Story Hagar of the Pawn-Shop

Hagar of the Pawn-Shop The Millionaire Mystery

The Millionaire Mystery The Mystery of a Hansom Cab

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab