- Home

- Fergus Hume

The Millionaire Mystery Page 6

The Millionaire Mystery Read online

Page 6

As he saw the handwriting, Mr Phelps started.

‘Upon my word, Alan, I don’t wonder Mrs Hester was deceived, especially when you consider her sight is not good! Why, I myself with my eyes should certainly take it for yours.’ (Mr Phelps wore pince-nez, but nevertheless resented any aspersion on his optical powers.) ‘But why on earth didn’t she telegraph to you?’

‘Well, you know how old-fashioned and conservative she is, sir. She makes out through the Scriptures—how, I cannot tell you—that the telegraph is a sinful institution. Therefore it is not to be wondered at that she trusted to the post. I got her letter only this morning as, of course, it followed me on from Bournemouth. Nevertheless, I knew about the loss of the key last night.’

‘Ah! the loss of the key. Yes, go on, Alan.’

‘Very well. Brown, being allowed to remain in my house, proceeded to make himself quite at home in the library. Mrs Hester, writing her letter—no easy task for her—took no further heed of him. He was in the room for quite an hour, and amused himself, it appears, in breaking open my desk. Having forced several of the drawers, he found at last the one he wanted—the one containing the key of the vault. Then he made all things beautifully smooth, so that Mrs Hester should not see they had been tampered with, and leaving a message that he would return to dinner, went out ostensibly for a walk. He returned, it appears, to his lodging, and left there again about nine o’clock in the evening. Since then nothing has been seen or heard of him.’

‘God bless me, Alan! are you sure he has the key?’

‘Positive. I looked in my desk last night and it was not there. But everything was done so nicely that I am strongly of the opinion that Mr Brown has served his apprenticeship as a cracksman, and that under a pretty good master too. No one but he could have stolen that key. Besides, the forged letter shows plainly that he came to the farm with no honest intentions. But what I can’t understand,’ continued Alan, biting his moustache, ‘is how the man came to know where the key was.’

‘Extraordinary—yes, that is extraordinary. Undoubtedly he it was who stole the body and gained access to the vault with your key. But the murder of Dr Warrender—’

‘He committed that too; I am convinced of it. Warrender called to see him, found he was out, and I have no doubt followed him. He probably saw Brown remove the body, and of course interfered, upon which the villain made short work of him. That is my theory, sir.’

‘And a very sound one, too, in many respects,’ said the Rector. ‘But Brown could not have removed the body alone. He must have had an accomplice.’

‘True; and it is for that very reason I am going to town this afternoon. Cicero Gramp may be able to supply some information on that point. It is quite possible he slept in the churchyard and saw the whole business—murder and all.’

‘Alan! Alan!’ cried Mr Phelps, horrified. ‘Do you believe this murder was committed on the sacred soil of the churchyard, in God’s own acre, Alan? No one, surely, could be so vile!’

‘I do, sir; and at the door of the vault. Brown, as you say yourself, cleverly concealed the body in Marlow’s coffin. He had no time to screw it down again, apparently. He must have had a pretty tough job to cut through that lead. He had to trust to chance, of course, that the vault would not be visited until he had got a safe distance away with his booty. And, indeed, but for Gramp’s letter, no one would ever have thought of going there. In fact, this Brown is a most ingenious and dangerous criminal.’

‘He is; indeed he is. But what could he possibly want the body for?’

‘Ha! that’s just it! I fancy this is a case of blackmail. If you remember, a millionaire’s body was stolen in America some few years ago, and only restored to the family on payment by them of a very large sum of money.’

‘Oh, that is what you think he is after?’

‘Yes, I do. It is highly probable, I think, that in a few weeks, or perhaps even in less time, we shall receive a letter demanding some thousands for the return of the body.’

‘But surely the police—’

‘Oh, Mr Brown will look after all that. You may depend upon it he’ll make himself quite safe before he goes that far. So talented a gentleman as he would not be likely to omit all necessary precautions of that kind.’

‘Humph!’ muttered Mr Phelps, considering, ‘and of Mrs Warrender’s suspicious flight, what think you?’

‘I confess I don’t know quite what to make of that. I have no great opinion of her as a woman; still, I should hardly credit her with being in league with this ruffian.’

‘No, indeed; for that, she must needs be the worst of women,’ said Mr Phelps with warmth. ‘Why, Alan, poor Warrender was simply crazy about her. He worked day and night to provide her with the finery she craved for. Besides, she seemed really fond of him.’

‘Who was she?’ asked Alan bluntly.

‘Well, I shouldn’t like to say it to everyone, Alan, but Mrs Warrender had been an actress.’

‘An actress! Under what name?’

‘That I cannot tell you. I called there one day and I heard her reciting Shakespeare. Her elocution seemed to me so fine that I complimented her upon it. Then she told me that she had been on the stage, and had retired when she married Warrender.’

‘That’s very strange! I always thought she had somewhat of a professional manner about her.’

‘And her hair, Alan! Flava coma—yellow hair; not that I mean, for one moment, she was what the Romans referred to by these words. Well, my boy, what is to be done now?’

‘I am going up to London in an hour’s time.’ Alan glanced at his watch while speaking.

‘But you’ll miss seeing Blair, the inspector,’ remonstrated Mr Phelps.

‘I’ll see him when I return: you can explain the case as well as I, sir. I shall bring Gramp back with me if I can manage it.’

‘And Mrs Warrender—shall I tell Blair about her?’

‘I fear you must. But let him be circumspect. It is not necessary to take any steps against her until we are tolerably sure of the reason for her sudden flight. When do they hold the inquest on Warrender?’

‘Tomorrow.’

‘Well, I’ll be back tonight and tell you what I’ve done.’ And Alan rose to go.

‘One moment, my dear boy. What about Sophy?’

‘I’ve seen her, and, of course, I was judicious in what I told her. She knows nothing about the loss of the key and my suspicions of Brown, although, funnily enough, she herself suspects him.’

‘Bless me! On what grounds can she do that?’

‘Oh, on the purely feminine grounds that she suspects him. She declares she will not marry me until her father’s body is discovered.’

‘Very right; very proper. I quite agree with her. You should start your married life with an absolutely clean sheet, Alan.’

The young man nodded, and as he left the inn he delivered himself of one warning.

‘Whatever you do, keep your eye on Joe Brill,’ he said significantly.

‘Why—why? What for?’

‘Because I fancy he knows a good deal more than he is inclined to tell,’ replied Alan.

Then, without further comment, he drove off, leaving the Rector considerably bewildered at this abrupt interpolation of a fresh name into the persons of the drama.

Meanwhile, Alan caught his train, and in due time, or a very fair approach to it, arrived in London. He took a hasty lunch at Waterloo, and drove to Westminster Bridge. Here he dismissed his cab, and set about inquiring for Dixon’s Rents. The slum—its name was highly suggestive of its being such—appeared to be well known. The first constable he asked was both familiar with and communicative about it.

‘It’s within easy distance of Lambeth Palace, sir,’ he said. ‘A bit rough by night, but you’ll be all right there in the daytime. Ask any constable near by the Palace, sir, and he’ll put you right. Thank you, sir.’

Alan left the officer of the law well pleased with his unlooked-for half-crown, an

d walked on towards the Palace. The second constable could not leave his beat, but the bestowal of another half-crown elicited from him the practical suggestion that a certain young shoeblack of repute should act as guide. The shoeblack was quite near at hand, and very shortly was enrolled as guide for the occasion. Together he and Alan started off, leaving the constable well content, though withal a trifle mystified, not to say curious.

The shoeblack led the way, and Alan followed closely. They turned away from the river into a mass of houses, where the streets became more and more squalid, and the population more and more ragged and unkempt. At length, after many twistings and turnings, they arrived at the entrance to a narrow cul-de-sac, and he was informed that this was his destination. He rewarded and dismissed the shoeblack, and proceeded down the dirty lane. Almost the first person he saw was a tall woman standing at the entrance of the court, closely veiled. She seemed to be hesitating whether she would come on or not. Then, suddenly, she threw up her veil. As she did so Alan uttered an exclamation of surprise.

It was Mrs Warrender!

CHAPTER VII

IN DIXON’S RENTS

AT the sound of Alan’s voice Mrs Warrender started like a guilty thing. He was astonished beyond measure at finding her in the same unsavoury neighbourhood as himself, bound, for all he knew, on the same errand. At all events, it was surely more than a coincidence that she should be on the threshold of Gramp’s dwelling, so to speak.

‘Mrs Warrender,’ he said, gravely lifting his hat, ‘this is indeed a surprise. Of course, you know what has happened at Heathton?’

‘I know all,’ answered the woman, in a rich, low voice. ‘Jarks, the sexton, told my servant this morning what has happened to poor Julian, and that his body has been found in the Marlow vault.’

‘Are you sure you did not know of it last night?’ asked Alan quietly.

‘Mr Thorold!’

The colour rushed to her face.

‘I mean that the letter which disturbed you so much might have hinted at the murder.’

‘A letter? How do you know I got a letter last night?’

‘The Rector called to break the news to you this morning, and your servant told him that you already knew it; also that you had left for London—with your jewels, Mrs Warrender,’ added Alan significantly.

‘And you followed me!’ cried the woman savagely. ‘Do you intend to accuse me of my husband’s murder?’

‘I certainly do not; and I did not follow you. I am here on the same errand as yourself.’

She looked terrified.

‘How do you know what my errand is?’

‘Because I can put two and two together, Mrs Warrender. I also received a letter—at least, Miss Marlow did, and from the same man—the man who lives here.’

‘Cicero Gramp?’

‘That is the name. You see, I was right. Does he intend to blackmail you also, and did you bring your jewels to satisfy his demands?’

She looked down the court. They were comparatively alone. A few ragged children were playing about, and some slatternly women were watching them from doorways. A man or two, brutalized by drink, hovered in the distance. But a smart constable, who passed and repassed the entrance of the cul-de-sac, casting inquisitive glances at Alan and his companion, kept these birds of prey from any nearer approach. Finding that they were out of earshot, Mrs Warrender produced a letter and handed it to Alan. It was written on the same thick, creamy paper, and in the same elegant handwriting as had been the communication to Sophy. He read it in silence. As he had expected, it informed Mrs Warrender that her husband was dead, and that Cicero Gramp, on payment of two hundred pounds, could inform her where the body could be found. His price had evidently gone up. But what struck Alan most was the nature of the information now offered. Cicero declared that he could tell the widow where her husband’s body was to be found. The body had already been discovered in the Marlow vault. Ergo, Cicero Gramp knew it was there. If so, had he seen the murder committed and the body taken into the vault? It seemed probable. Indeed, it seemed likely that he could solve the whole mystery; but, strangely enough, the prospect did not seem to afford Mr Thorold much satisfaction. He handed back the letter with a dissatisfied smile.

‘I think you have wasted your time coming up,’ he said. ‘Jarks, no doubt, told your servant that the doctor’s body had already been discovered. Why, then, come up to pay blackmail?’

‘I want to find out who killed Julian,’ she said.

‘Then you are on your way to see this man?’

‘Yes.’ She shuddered. ‘But this terrible place. I am afraid.’

‘Then why come here? I am going to see Mr Gramp on Miss Marlow’s behalf. If you like, I will represent you also.’

‘No, thank you; I must see him myself.’

‘Very well. I suppose you are not staying in town?’

‘Yes, at the Norfolk Hotel. I shall remain until tomorrow, so as to sell my jewels and bribe this man.’

‘There will be no need to sell your jewels,’ said Alan soothingly. ‘I will be responsible for the blackmail. Have you the jewels with you?’

‘No, I dared not bring them. He might have robbed me. They are in my bedroom at the hotel.’

‘Then go back at once and look after them. I will bring this man there in, let us say, an hour.’

‘Thank you, Mr Thorold,’ she said. ‘I accept your offer. I am really afraid to go down that slum.’

He gazed after her fine figure as she walked hurriedly away. Somehow that haughty air and resolute gait did not fit in well with her expression of fear. It was curious. He felt there was something strange about Mrs Warrender. However, she had been open enough with him, so he did not choose to think badly of her.

The man he sought was not easy to find. Mr Gramp had his own reasons for keeping clear of the police. The whole alley was known by the name of Dixon’s Rents, and Thorold had no idea in which of the houses to ask for him. He questioned a stunted street arab with wolfish eyes, emphasizing his request with a sixpence.

‘Oh, Cicero!’ yelped the lad, biting the coin. ‘Yuss, he’s round about. Dunno! Y’ain’t a ’tec?’

‘What’s that?’

‘A de-tec-tive,’ drawled the boy. ‘Cicero ain’t wanted, is he?’

‘Not by me. Is Cicero generally—er—wanted?’ inquired Alan delicately.

The urchin closed one eye rapidly, and grinned with many teeth. But, instead of replying he took to shouting hoarsely for ‘Mother Ginger’. The surrounding population popped out of their burrows like so many rabbits, and for the next few minutes ‘Mother Ginger’ was asked for vigorously. Alan looked round at the ragged, blear-eyed slum-dwellers, but could see nothing of the lady in question. Suddenly his arm was twitched, and he turned to find a dwarf no higher than his waist trying to attract his attention. Mother Ginger, for it was she, had a huge head of red hair, fantastically decked with ribbons of many colours. Her dress, too, was rainbow-hued, like Joseph’s coat. She had carpet slippers on her huge feet, and white woollen gloves on her large hands. Her face was as large as a frying-pan and of a pallid hue, with expressionless blue eyes and a big mouth. Alan saw in her a female Quasimodo.

‘Wot is it?’ she inquired. Evidently Mother Ginger was vain of her finery and of the attention she attracted. ‘Is it Mr Gramp you want, m’dimber-cove?’

‘Yes. Can you take me to him?’ asked Thorold, wincing at the penny-whistle quality of her voice. ‘Is he at home?’

‘P’r’aps he is, p’r’aps he ain’t,’ retorted Mother Ginger, with a fascinating leer. ‘Wot d’ye want with him?’

‘This will explain.’ And Alan put Cicero’s letter into her hand. ‘Give him that.’

She nodded, croaked like a bull-frog, and vanished amongst the crowd. Mr Thorold found himself the centre of attraction and the object of remark.

This somewhat unpleasant position was put an end to by the appearance of Mother Ginger, who clawed Alan, and drew him into a house at the

end of the court. The tatterdemalions gave a yell of disappointment at the escape of their prey, and their prey congratulated himself that he had not made his visit at night. He felt that he might have fared badly in this modern Court of Miracles. However, it appeared that he was safe under the protection of Mother Ginger. With the activity of a monkey, she conducted him up a dirty staircase and into a bare room furnished with a bed, a chair, and a table. Here Alan was greeted by a bulky creature in a gorgeous red dressing-gown, old and greasy, but still pretentious. He had no difficulty in recognizing the man whom he had seen reciting on the parade at Bournemouth.

‘I welcome you, Mr Thorold,’ said Cicero in his best Turveydrop style. ‘Mother Ginger, depart.’

To get rid of the woman, Mr Thorold placed a shilling in her concave claw, upon which she executed a kind of war-dance, and vanished with a yelp of delight. Left alone with the pompous vagabond, the young man took the only chair, and faced his host, who was sitting majestically on the bed, his red dressing-gown wrapped round him in regal style.

‘So you are Cicero Gramp?’ began Alan. ‘I have seen you—’

‘At Bournemouth,’ interrupted the professor of elocution and eloquence. ‘True, I was there for the benefit of my health.’

‘And to blackmail Miss Marlow.’

‘Blackmail—a painful word, Mr Thorold.’

‘How do you know my name?’

‘It is part of my business to know all names,’ was the answer—‘ex nihilo nihil fit, if you understand the tongue of my namesake. If I did not know what I desire to know, my income would be small indeed. I visited the salubrious village of Heathton, and learned there that Miss Marlow and Mr Thorold, to whom she was engaged, were recreating themselves at the seaside with an inferior companion. Bournemouth was the seaside, and I went there. On seeing a young lady with a spinster and a gentleman in attendance, I noted Miss Marlow, Mr Thorold, and Miss Parsh.’

‘And made yourself scarce?’

‘I did,’ admitted Cicero frankly. ‘I departed as soon as you were out of sight, knowing that my letter would be delivered, and that you might call in the police.’

The Crowned Skull

The Crowned Skull Madame Midas

Madame Midas The Opal Serpent

The Opal Serpent The Solitary Farm

The Solitary Farm The Mystery Queen

The Mystery Queen The Bishop's Secret

The Bishop's Secret Red Money

Red Money The Red Window

The Red Window The Pagan's Cup

The Pagan's Cup The Third Volume

The Third Volume A Coin of Edward VII: A Detective Story

A Coin of Edward VII: A Detective Story Hagar of the Pawn-Shop

Hagar of the Pawn-Shop The Millionaire Mystery

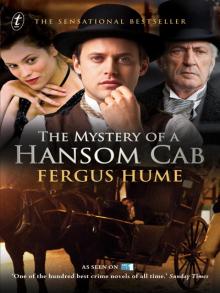

The Millionaire Mystery The Mystery of a Hansom Cab

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab