- Home

- Fergus Hume

The Pagan's Cup Page 7

The Pagan's Cup Read online

Page 7

CHAPTER VII

A NINE DAYS' WONDER

Ill news spreads like circles on water when a stone is thrown in.Barker, the old sexton, a white-haired, crabbed sinner, was the first todiscover the loss. He had gone to the chapel at seven in the morning tomake ready the church for early celebration, and on going to the altarhe had noticed that the cup was missing. Nothing else had been touched.At once the old man had trotted off to see the vicar, and in a quaveringvoice related what had taken place, finishing with a hope that he wouldnot be blamed for the loss.

"You locked the chapel up last night?" asked Mr Tempest, sorelydistressed, for indeed this was sacrilege and not a common robbery.

"'Deed and I did!" replied Barker, sturdily. "And I took the key homewith me. My wife saw me place it on its nail just inside the door."

"Was the church door locked?"

"Fast locked, sir. And all the windows fastened. I went round the chapelto see if I could find any sign."

"When did you leave the church last night, Barker?"

"At nine o'clock, after I made everything right for the night. It wasafter evening service, if you mind, Mr Tempest. Then I went home and putthe key in its place. My Joan and I went then to a neighbour for a bitof supper. We got home again about eleven."

"And the key was still on its nail?"

"Well, sir," said Barker, scratching his white locks, "I didn't look.But it was there this morning; so it could not have been taken away.Besides, my Joan locked the door of our cottage. No one could have gotin."

"The cup was on the altar when you left the church last night?"

"On the altar where it ought to be. But this morning it's nowhere to beseen. I hope you don't think it's my fault, sir."

"No," replied Mr Tempest. "I cannot see that you are to blame. But thisis a very serious matter, Barker. I did not know that there was anyonein Colester who would have committed such a crime."

"It's terrible," sighed the sexton. "And what that poor lass Pearl willsay I don't know."

"She must not hear of it," said Raston, who entered at the moment. "Shethinks so much of the cup that in her present state of health its lossmay do her much harm."

"Is she very ill, Raston?"

"Yes, sir. Much worse than she was last night. But Mrs Jeal is givingher all attention, and I have sent Dr James. But about this loss, sir?"

"We had better go to the chapel, Raston, and see with our own eyes."

Followed by Barker, still protesting that it was not his fault, thevicar and the curate went up to the church. It was surrounded with acrowd of people, for the news had spread quickly. Some looked in at thedoor, but no one had ventured to enter, as each one was afraid if he didan accusation might be levelled against him. Mr Tempest told Harris, thelocal policeman, to keep back the crowd, and entered the chapel followedby his curate. All was as Barker had said. There was the altar coveredwith its white cloth, and with the withered flowers still in the vases.The gilded crucifix was also there; but not a sign of the cup. It hadvanished entirely. Tempest sighed.

"A terrible thing for the man who stole it," he muttered. "This is nocommon robbery. Raston, let us examine the church."

The two went round it carefully, but could find nothing for a long timelikely to enlighten them as to the cause of the robbery. Then in thelepers' window, a small opening at the side of the chancel, Rastondiscovered that some of the stones had been chipped. "I believe thechurch was entered through this window," said Raston, but the vicar wasinclined to doubt.

"The window is so small that no grown man could have got through," hesaid.

They went outside, and certainly against the wall and immediately underthe window were marks, and scratches of boots, as though someone mighthave climbed the wall. Also the sides of the window were broken, asthough a way had been found through. The lepers' window was so smallthat no care had been taken to put in glass or iron bars. Besides, noone had ever expected that the chapel would be robbed. In all itscenturies of history nothing up till now had ever been taken from it.And now the most precious thing of all had vanished!

"And during my occupation of the Vicarage," said Mr Tempest. "It isreally terrible!"

However, in spite of the loss, he held the service as usual, and as agreat number of people, attracted by the news of the robbery, had come,the chapel was quite full. Service over, Tempest returned to theVicarage, and found Mr Pratt waiting to see him.

"This is a nice thing!" said Pratt, looking annoyed, as well he might,seeing that his magnificent gift had disappeared. "I did not know thatyou had thieves in the parish, Mr Tempest!"

"Neither did I," groaned the vicar, sitting down. "Hitherto we have beensingularly exempt from crime. And now one of the very worst sort hasbefallen us! Not a mere robbery, Mr Pratt. Sacrilege, sir, sacrilege!"

The American turned rather white as Tempest spoke. He had not regardedthe robbery save as a common one. The idea that it was sacrilege placedit in a new light. Yet Mr Pratt was sharp enough to have guessed thisbefore. The wonder was that he had not done so.

"What are you going to do?" he asked, after a pause.

"Raston has sent for the police at Portfront. I expect the inspectorwill come over this afternoon."

Pratt shrugged his shoulders. "I don't think much of the police," hesaid. "The metropolitan detectives are stupid enough; but the provincialpolice--oh, Lord! I beg your pardon, Mr Tempest; I forgot myself."

"No matter, no matter," said Tempest, wearily. "I can think of nothingsave our great loss. And your gift, too, Mr Pratt! Terrible!"

"Well," said the American, cheerfully, "if this cup can't be found, Iguess I must find you another one."

"The cup _shall_ be found," cried the vicar, vehemently. "The culpritmust belong to this parish, else he would not have known the lepers'window in the chapel. We shall find the guilty person yet, Mr Pratt."

"I hope so," said Pratt, with another shrug; "but he seems to have gotaway very cleverly. I shall see you this afternoon when you interviewthe inspector, Mr Tempest. I should like to have a hand in thediscovery."

"Certainly, certainly. Who but you, the giver of the cup, should wish tohelp? Come here this afternoon, Mr Pratt."

As Pratt left the Vicarage he met Sybil, who looked sad. "Don't take onso, Miss Tempest," he said; "we'll find the cup yet."

"I was not thinking so much of that," explained Sybil; "but this morningmy poor dear Leo went away."

"When is he coming back?"

"Towards the end of next week. I wonder who can have taken the cup?"

Pratt sneered, an unusual thing for so good-natured a man. "No doubt thePortfront police will tell us," he said; "but I haven't much opinion oflaw officers myself, Miss Sybil. I once lost a lot of gems in London,and the thief was never found. Are you fond of gems? Come to my houseand I'll show you my collection. I have several thousand pounds' worth."

"Is it not dangerous to keep them in your house after this robbery?"

Pratt laughed. "I don't think a thief would steal them so easily as thecup!" he laughed. "I have a good dog and a capital revolver. No, MissSybil, I can look after my property well, I assure you."

When he went away Sybil sighed and sought her room. The departure of Leohad left her very sad. She did not know what would become of him. Hewould pay his debts and then enlist for South Africa. In that case shewould not see him again for months. Perhaps never--for it might be thatsome bullet would lay him low on the veldt. However, for the sake of herfather, she strove to assume a light-hearted demeanour. The vicar feltthe loss of the cup keenly. And although Sybil thought he had treatedher hardly in her love affair, she laid all thoughts of self aside so asto comfort him in his trouble.

As for Pratt, he walked back to his own house. At the foot of the CastleHill he met Mrs Gabriel, who seemed to be in a great state ofindignation. As usual, her anger was directed against Leo.

"He came to me last night and said that he was going up to London to payhis debts. This morning he went off at seven

without taking leave. Now,Mr Pratt, you have been giving him the money to pay his debts."

"Indeed I have not, Mrs Gabriel," said Pratt, quite prepared for thisquestion. "I have not given him a sixpence."

"Then where did he get so large a sum?" asked the lady, anxiously.

"I don't know. He told me that someone had lent it to him."

"A likely story! As if anyone here would trust him with money without aguarantee! Mr Pratt--" Here Mrs Gabriel stopped and her face went white.A thought had struck her and she was about to speak. But she savedherself in time and stared at her companion.

"What is the matter?" said Pratt, anxiously. He thought she would faint,a weakness he had never hitherto associated with Mrs Gabriel.

"Nothing," she replied in a strangled voice. "But Leo--I must seeFrank," and without another word she hurried away.

Pratt stared after her as he could not conjecture what she meant. Thenhe shrugged his shoulders and went back to The Nun's House. That sameafternoon he called again at the Vicarage, and there found Mr Tempest inconsultation with a grey-haired man whom he introduced as InspectorGerman. The police officer, who had a shrewd face with keen eyes, noddedin a friendly manner. "I understand you gave this cup to the chapel, MrPratt," he said. "Pity it is lost."

"A great pity," replied Pratt, who was making a thorough examination ofthe man, and now seemed much more at ease than when he had entered. "Ihope the thief has gone away, however. I have in my house severalthousand pounds' worth of gems, and I don't want him to come afterthem."

"How do you know it was a man?" asked German, quietly.

"I don't know," responded the American, with a stare and a laugh. "Ionly speak as others do. For my part, I believe that there were twopeople concerned in the robbery--a man and a boy."

"Certainly a boy," replied Tempest, looking up. "No one but a small boycould have forced himself through that window."

"Then you don't think, Mr Tempest, that a woman can have had anything todo with the matter?"

Tempest stared. The idea seemed ridiculous. "I do not think a womanwould commit so wicked an act," he said stiffly.

"Oh, as to that," interposed Pratt, "women are as wicked as men, andworse when the fit takes them. But I see what Mr Inspector means. He hasheard of Pearl Darry's devotion to the cup."

"It was not Pearl!" cried Mr Tempest, indignantly. "I am sure of that.Why, the poor child regarded that cup as something too holy to betouched--as it was," added the vicar, reverently.

"Well," said German, after a pause, "I have been talking to yourvillagers about her. It seems that she was always haunting the chapeland looking at the cup. She might have been seized with a desire to haveit for her very own. She is insane, I believe, and insane people havevery mad ideas. Also she is small and could easily have forced herselfthrough the lepers' window, of which she would know the position."

Pratt looked with contempt at the officer. He was even more stupid thanhe had given him credit for. "You can rest easy, Mr Inspector," he said."It was not Pearl who stole my cup. She has been ill in bed for the lastfew days and unable to move, as Mrs Jeal and Dr James will tell you."

"I must make certain of that myself," said the inspector. "Will you comewith me, Mr Pratt?"

"Not I," replied the American. "I think you are going on a wild-goosechase. The best thing for you to do, Mr Inspector, is to see if anyvagabonds have been in the village lately."

"I have already done so," replied German, coolly; "and the villagersassure me that no stranger has been seen hereabouts for some days.However, I am willing to give this girl the benefit of the doubt. But Imust see her."

As Pratt still refused to come and Tempest was unwilling to call at thecottage of Mrs Jeal on such an errand, the inspector went himself. Hefound no difficulty in entering, as Raston was at the door. All thesame the curate was indignant on hearing the accusation. He took Germaninto the sitting-room, but refused--and in this he was backed up by thedoctor--to let the inspector enter the bedroom of the sick girl. Notthat German desired to do so after an interview with Mrs Jeal. She wasmost indignant at the slur cast upon the character of the girl shecalled her adopted daughter. There was a scene, and Mrs Jeal provedherself to be more than equal to the official from Portfront.

"I never heard anything so wicked in my life," cried Mrs Jeal. "The poorchild may be mad, but not mad enough to take what is not her own. Iwonder at you, sir, that you should come here on such an errand."

"My duty is clearly before me," replied the inspector, stiffly. "Is thegirl really and truly ill?"

"You can take my word for that, Mr German," said Raston. "Or, if you donot believe me, here is Dr James!"

"Ill!" repeated the doctor, when the question was put to him. "She had abad attack of inflammation of the lungs, and she is worse this morningthan I have ever seen her. I do not wish her disturbed, Mr Inspector."

"She could not have gone out last night to the chapel, doctor?"

"Not without the risk of being dead this morning," replied James, dryly."Besides, Pearl Darry is not a thief. No, sir. Whosoever stole that cup,it was _not_ my patient."

"And I would have you know," cried Mrs Jeal, with her arms akimbo, "thatI sat beside her the most of last night, and not one step did she stiroff the bed."

"Ah, well," said German, who could not go against this evidence, "it isvery plain that I am in the wrong. Unless--"

"There's no _unless_ about it, sir," cried Mrs Jeal. "Pearl wasna oot o'this hoose;" in her excitement she was falling into the Scotch speech ofher childhood. "I wonder at ye, I do that! Hoots, awa' wi' ye!"

Baffled in this quarter, the inspector took his way into the village.First he examined the chapel. Then he started out to make inquiries. Forquite three days he exasperated everyone in the village with hisquestions and suspicions. But for all his worry he was unable to get atthe truth. No tramps had been to the village. Old Barker proved hisinnocence with the assistance of a wrathful wife, and there was not asingle person to whom the well-meaning but blundering inspector couldpoint as likely to have stolen the cup. Finally, he was obliged to statethat he could do nothing, and withdrew himself and his underlings fromColester, much to the relief of the villagers, whom he had grievouslyoffended by his unjust suspicions. The cup had vanished as though it hadbeen swallowed up by the earth, and no one was able to say who had takenit.

"A grievous loss," sighed Mr Tempest, when he became resigned. "But Isorrow not so much for the theft of the cup as for the awful sacrilegeof which the thief has been guilty." And he took occasion to refer tothe terrible deed in a wrathful sermon. The villagers shook in theirshoes when they heard of the ills likely to befall the thief. But notone was able to say who was guilty.

For a whole week things went on much as usual, and the excitement diedaway. Leo was still in London, and, through Pratt, Sybil had heard fromhim. He had seen his creditors and had settled all his debts. He was nowthinking about enlisting. Before he could do so, however, Sybil sent amessage recalling him to Colester to defend his good name.

It so happened that Barker held his tongue for some time, but when thefirst effects of the fright lest he might be accused passed away, hebegan to talk. The old man was given to babbling in his cups. Thus itcame about that he mentioned that he believed Mr Haverleigh had takenthe cup. It seemed that Barker had seen Leo near the chapel, as he wasleaving it about half-past nine. Mr Haverleigh, said the old man, hadseemed to shun recognition, and had hurried past him. Not thinkinganything of the matter, Barker had left him near the chapel door. Now,however, he hinted that Leo might have had some reason to be there at sountoward an hour. Also, he had gone away the next morning early. It waswell known in Colester that the young man was in debt, and that hismother had refused to pay his debts. What, then, was more likely, peopleargued, than that Leo should have stolen the cup, should have taken itup to London before the loss was discovered, and should have sold it topay his debts? In a few hours this sorry tale was all over the place,and so came to Sybil's ears. It

was her father who heard it, and herfather who told her.

"But surely you do not believe it!" cried the girl, when the accusationwas made. "You have known Leo all these years! Whatever you may haveagainst him, father, you know that he would never commit so wicked anact."

"I say nothing until I hear what _he_ has to say," replied the vicar,who, for some reason, seemed to be biased against Leo. "But you mustadmit that it was strange he should be near the chapel at so late anhour. And we know that he is deeply in debt. Mrs Gabriel told me herselfthat he owed three hundred pounds. In a moment of madness--"

"I won't hear a word against Leo!" interrupted Sybil, pale but resolute."Not if an angel came down to accuse him would I believe him guilty! Howcould he have got the key? And if he did not get the key, how could hehave forced himself through that small window?"

"I say nothing until I hear his defence," said the vicar, obstinately;"but the whole affair is highly suspicious."

"I never knew you to be unjust before, father," cried Sybil. "MrsGabriel has infected you with her dislike of Leo. I shall say nothingmyself, although I could say more than you think. But I shall send atonce to Leo, and he shall come back to rebut this wicked accusation."

Without listening to another word, Sybil ran off to see Pratt, who wasequally indignant. "It is disgraceful," he said furiously. "Leo neverwould do such a thing, never! Be comforted, my dear. I'll ride over toPortfront this very day and send a wire to him."

And this he did without delay. More than that, he defended Leo heartilywhen he returned; so did Raston. Hale kept silent. But the majority ofthe villagers were against the young man. Leo returned in disgrace.

The Crowned Skull

The Crowned Skull Madame Midas

Madame Midas The Opal Serpent

The Opal Serpent The Solitary Farm

The Solitary Farm The Mystery Queen

The Mystery Queen The Bishop's Secret

The Bishop's Secret Red Money

Red Money The Red Window

The Red Window The Pagan's Cup

The Pagan's Cup The Third Volume

The Third Volume A Coin of Edward VII: A Detective Story

A Coin of Edward VII: A Detective Story Hagar of the Pawn-Shop

Hagar of the Pawn-Shop The Millionaire Mystery

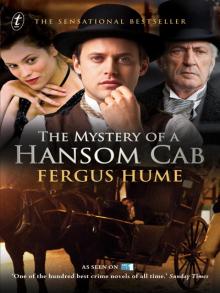

The Millionaire Mystery The Mystery of a Hansom Cab

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab