- Home

- Fergus Hume

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab Page 8

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab Read online

Page 8

‘Oh, no you won’t,’ said the landlady, tossing her head, ‘me not ’avin’ a knocker, an’ your ’and a-scratchin’ the paint off the door, which it ain’t bin done over six months by my sister-in-law’s cousin, which ’e is a painter, with a shop in Fitzroy, an’ a wonderful heye to colour.’

‘Does Mr Fitzgerald live here?’ asked Mr Gorby, quietly.

‘He do,’ replied Mrs Sampson, ‘but ’e’s gone out, an’ won’t be back till the arternoon, which any messige ’ull be delivered to ’im, punctual on ’is arrival.’

‘I’m glad he’s not in,’ said Mr Gorby. ‘Would you allow me to have a few moments’ conversation?’

‘What is it?’ asked the cricket, her curiosity being roused.

‘I’ll tell you, when we get inside,’ answered Mr Gorby.

The cricket looked at him with her sharp little eyes, and, seeing nothing disreputable in him, led the way up stairs, crackling loudly the whole time. This so astonished Mr Gorby that he cast about in his own mind, for an explanation of the phenomena.

‘Wants oiling about the jints,’ was his conclusion, ‘but I never heard anything like it, and she looks as if she’d snap in two, she’s that brittle.’

Mrs Sampson took Gorby into Brian’s sitting-room, and having closed the door, sat down and prepared to hear what he had to say for himself.

‘I ’ope it ain’t bills,’ she said, ‘Mr Fitzgerald ’avin’ money in the bank, and everythin’ respectable like a gentleman as ’e is, tho’, to be sure, your bill might come down on him unbeknown, ’e not ’avin’ kept it in mind, which it ain’t everyone as ’ave sich a good memory as my aunt on my mother’s side, she ’avin’ bin famous for ’er dates like a ’istory, not to speak of ’er multiplication tables and the numbers of people’s ’ouses.’

‘It’s not bills,’ answered Mr Gorby, who, having vainly attempted to stem the shrill torrent of words, had given in and waited mildly until she had finished, ‘I only want to know a little about Mr Fitzgerald’s habits.’

‘And what for?’ asked Mrs Sampson, with an indignant cackle, ‘are you a noospaper a-puttin’ in articles about people who don’t want to see ’emselves in print, which I knows your ’abits, my late ’usband ’avin’ bin a printer on a paper which bust up, not ’avin the money to pay wages, thro’ which, there was doo to him the sum of one pound seven and sixpence halfpenny, which I, bein’ ’is widder, ought to ’aye, not that I expects to see it on this side of the grave—oh, dear no!’ and she gave a shrill, elfish laugh.

Mr Gorby, seeing that unless he took the bull by the horns he would never be able to get what he wanted, grew desperate, and plunged in medias res.

‘I am an insurance agent,’ he said, rapidly, so as to prevent any interruption by the cricket, ‘and Mr Fitzgerald wants to insure his life in our company; before doing so, I want to find out if he is a good life to insure; does he live temperately? keep early hours? and, in fact, all about him.’

‘I shall be ’appy to answer any enquiries which may be of use to you, sir,’ replied Mrs Sampson, ‘knowin’ as I do, ’ow good a insurance is to a family, should the ’ead of it be taken off unexpected, leavin’ a widder, which as I know, Mr Fitzgerald is a-goin’ to be married soon, and I ’opes ’ull be ’appy, tho’ thro’ it I loses a lodger as ’as allays paid reg’lar, and be’aved like a gentleman.’

‘So he is a temperate man?’ said Mr Gorby, feeling his way cautiously.

‘Not bein’ a blue ribbing all the same,’ answered Mrs Sampson, ‘and I never saw ’im the wuss for drink, ’e bein’ allays able to use his latch key and take ’is boots off afore going to bed, which is no more than a woman ought to expect from a lodger, she ’avin’ to do ’er own washin’.’

‘And he keeps good hours?’

‘Allays in afore the clock strikes twelve,’ answered the landlady, ‘tho’, to be sure, I uses it as a figger of speech, none of the clocks in the ’ouse strikin’ but one, which is bein’ mended, ’avin’ broke through overwindin’.’

‘Is he always in before twelve?’ asked Mr Gorby, keenly disappointed at this answer.

Mrs Sampson eyed him waggishly, and a smile crept over her wrinkled little face.

‘Young men, not bein’ old men,’ she replied, cautiously, ‘and sinners not bein’ saints, it’s not nattral as latch keys should be made for ornament instead of use, and Mr Fitzgerald bein’ one of the ’ansomest men in Melbourne, it ain’t to be expected as ’e should let ’is latch key git rusty, tho’, ’avin’ a good moral character, ’e uses it with moderation.’

‘But I suppose you are generally asleep when he comes in late?’ said the detective, ‘so you can’t tell what hour he comes home?’

‘Not as a rule,’ assented Mrs Sampson, ‘bein’ a ’eavy sleeper, and much disposed for bed, but I ’ave ’eard ’im come in arter twelve, the last time being Thursday week.’

‘Ah!’ Mr Gorby drew a long breath, for Thursday week was the night when the murder was committed.

‘Bein’ troubled with my ’ead,’ said Mrs Sampson, ‘thro’ ’avin’ been out in the sun all day a-washin’, I did not feel so partial to my bed that night, as in general, so went down to the kitching with the intent of getting a linseed poultice to put at the back of my ’ead, it being calculated to remove pain, as was told to me when a nuss by a doctor in the horspital, ’e now bein’ in business for hisself at Geelong with a large family, ’avin’ married early. Just as I was leavin’ the kitching, I ’eard Mr Fitzgerald a-comin’ in, and, turnin’ round, looked at the clock, that ’avin’ been my custom when my late ’usband came in in the early mornin’, I bein’ a-preparin’ ’is meal—’

‘And the time was?’ asked Mr Gorby, breathlessly.

‘Five minutes to two o’clock,’ replied Mrs Sampson.

Mr Gorby thought for a moment.

‘Cab was hailed at one o’clock—started for St Kilda at about ten minutes past—reached grammar school, say at twenty-five minutes past—Fitzgerald talks five minutes to cabman, making it half past—say he waited ten minutes for other cab to turn up, makes it twenty minutes to two—it would take another twenty minutes to get to East Melbourne—and five minutes to walk up here—that makes it five minutes past two instead of before—confound it—was your clock in the kitchen right?’ he asked, aloud.

‘Well, I think so,’ answered Mrs Sampson. ‘It does get a little slow sometimes not ’avin’ bin cleaned for some time, which my nevy bein’ a watchmaker I allays ’ands it over to ’im.’

‘Of course it was slow on that night,’ said Gorby triumphantly, ‘he must have come in at five minutes past two—which makes it right.’

‘Makes what right,’ asked the landlady sharply, ‘and ’ow do you know my clock was ten minutes wrong?’

‘Oh, it was, was it?’ asked Gorby eagerly.

‘I’m not denyin’ that it wasn’t,’ replied Mrs Sampson, ‘clocks ain’t allays to be relied on more than men an’ women—but it won’t be anythin’ agin ’is insurance will it as in general ’es in afore twelve.’

‘Oh, all that will be quite safe,’ answered the detective, delighted at having obtained the required information. ‘Is this Mr Fitzgerald’s room?’

‘Yes, it is,’ replied the landlady, ‘but ’e furnished it ’imself, bein’ of a luxurus turn of mind, not but what ’is taste is good, tho’ far be it from me to deny I ’elped ’im to select—but avin’ another room of the same to let any friends as you might ’ave in search of a ’ome ’ud be well looked arter, my references bein’ very ’igh an’ my cookin’ tasty—an’ if—’

Here a ring at the front door bell called Mrs Sampson away, so with a hurried word to Gorby she crackled downstairs. Left to himself, Mr Gorby arose and looked round the room. It was excellently furnished, and the pictures on the wall were all in good taste. There was a writing table at one end of the room under the window, which was covered with papers.

‘It’s no good looking for the papers he took out of

Whyte’s pocket, I suppose,’ said the detective to himself, as he turned over some letters. ‘As I don’t know what they are and couldn’t tell them if I saw them—but I’d like to find that missing glove and the bottle that held the chloroform—unless he’s done away with them—there doesn’t seem any sign of them here, so I’ll have a look in his bedroom.’

There was no time to lose as Mrs Sampson might return at any moment, so Mr Gorby walked quickly into the bedroom, which opened off the sitting-room. The first thing that caught the detective’s eye was a large photograph of Madge Frettlby in a plush frame, which stood on the dressing-table. It was the same kind as he had already seen in Whyte’s album, and he took it up with a laugh.

‘You’re a pretty girl,’ he said, apostrophising the picture, ‘but you give your photograph to two young men, both in love with you, and both hot-tempered—the result is that one is dead, and the other won’t survive him long—that’s what you’ve done.’

He put it down again, and looking round the room caught sight of a light covert coat hanging behind the door and also a soft hat.

‘Ah,’ said the detective, going up to the door, ‘here is the very coat you wore when you killed that poor fellow—I wonder what you have in the pockets,’ and he plunged his hand into them in turn. There was an old theatre programme and a pair of brown gloves in one, but in the second pocket Mr Gorby made a discovery—none other than that of the missing glove. There it was—a soiled white glove for the right hand, with black bands down the back, and the detective smiled in a gratified manner, as he put it carefully in his pocket.

‘My morning has not been wasted,’ he said to himself. ‘I’ve found out that he came in at a time which corresponds to all his movements after one o’clock on Thursday night, and this is the missing glove, which clearly belonged to Whyte—if I could only get a hold of the chloroform bottle I’d be satisfied.’

But the chloroform bottle was not to be found, though he searched most carefully for it. At last, hearing Mrs Sampson coming up the stairs again, he desisted from his search and came back to the sitting-room.

‘Threw it away, I expect,’ he said, as he sat down in his old place, ‘but it doesn’t matter. I think I can form a chain of evidence, from what I have discovered, which will be sufficient to convict him, besides I expect when he is arrested he will confess everything, he seems to have such a lot of remorse for what he has done.’

The door opened, and Mrs Sampson crackled into the room in a state of indignation.

‘One of them Chinese ’awkers,’ she explained, ‘’e’s bin a-tryin’ to git the better of me over carrots—as if I didn’t know what carrots was—and ’im a-talkin about a shillin’ in his gibberish, as if ’e ’adn’t been brought up in a place where they don’t know what a shillin’ is—but I never could abide furreigners ever since a Frenchman as taught me ’is language made orf with my mother’s silver tea pot, unbeknown to ’er, it being set out on the sideboard for company.’

Mr Gorby interrupted these domestic reminiscences of Mrs Sampson’s by stating that now she had given him all necessary information, he would take his departure.

‘And I ’opes,’ said Mrs Sampson, as she opened the door for him, ‘as I’ll have the pleasure of seein’ you again should any business on be’alf of Mr Fitzgerald require it.’

‘Oh, I’ll see you again,’ said Mr Gorby, with heavy jocularity, ‘and in a way you won’t like, as you’ll be called as a witness,’ he added, mentally. ‘Did I understand you to say Mrs Sampson,’ he went on, ‘that Mr Fitzgerald would be at home this afternoon?’

‘Oh, yes sir, ’e will,’ answered Mrs Sampson, ‘a-drinkin’ tea with his young lady, who is Miss Frettlby, and ’as got no ’end of money, not but what I mightn’t ’ave ’ad the same ’ad I been born in a higher spear.’

‘You need not tell Mr Fitzgerald I have been here,’ said Gorby, closing the gate, ‘I’ll probably call and see him myself this afternoon.’

‘What a stout person ’e are,’ said Mrs Sampson to herself, as the detective walked away, ‘just like my late father, who was allays fleshy, being a great eater, and fond of ’is glass, but I took arter my mother’s family, they bein’ thin-like, and proud of keeping ’emselves so, as the vinegar they drank could testify, not that I indulge in it myself.’

She shut the door and went upstairs to take away the breakfast things, while Gorby was being driven along at a good pace to the police office, in order to get a warrant for Brian’s arrest on a charge of wilful murder.

CHAPTER TEN

IN THE QUEEN’S NAME

It was a broiling hot day—one of those cloudless days with the blazing sun beating down on the arid streets and casting deep black shadows. By rights it was a December day, but the clerk of the weather had evidently got a little mixed, and popped it into the middle of August by mistake. The previous week, however, had been a little chilly, and this delightfully hot day had come as a pleasant surprise and a forecast of summer.

It was Saturday morning, and of course all fashionable Melbourne was doing the Block. With regard to its ‘Block’, Collins Street corresponds to New York’s Broadway, London’s Regent Street and Rotten Row, and to the Boulevards of Paris. It is on the Block that people show off their new dresses, bow to their friends, cut their enemies, and chatter small talk. The same thing no doubt occurred in the Appian Way, the fashionable street of Imperial Rome, when Catullus talked gay nonsense to Lesbia, and Horace received the congratulations of his friends over his new volume of society verses. History repeats itself, and every city is bound by all the laws of civilisation to have one special street, wherein the votaries of fashion can congregate.

Collins Street is not of course such a grand thoroughfare as those above mentioned, but the people who stroll up and down the broad pavement are quite as charmingly dressed and as pleasant as any of the peripatetics of those famous cities. As the sun brings out bright flowers so the seductive influence of the hot weather had brought out all the ladies in gay dresses of innumerable colours, which made the long street look like a restless rainbow. Carriages were bowling smoothly along, their occupants smiling and bowing as they recognised their friends on the sidewalk; lawyers, their legal quibbles finished for the week, were strolling leisurely along, with their black bags in their hands; portly merchants, forgetting Flinders Lane and incoming ships, were walking beside their pretty daughters, and the representatives of swelldom were stalking along in their customary apparel of curly hats, high collars, and masher suits. Altogether it was a very pleasant and animated scene, and would have delighted the heart of anyone who was not dyspeptic, nor in love—dyspeptic people and lovers (disappointed ones of course) being accustomed to survey the world in a cynical vein.

Madge Frettlby was engaged in that pleasant occupation so dear to every female heart, of shopping. She was in Moubray, Rowan and Hicks turning over ribbons and laces, while the faithful Brian waited for her outside, and amused himself by looking at the human stream which flowed along the pavement. If there is one thing above another which is dreaded by men it is shopping with ladies, for then a few minutes with them becomes hours, and the weary husband, pensively smoking cigarettes outside, while his better half worries the young man at the counter about the last new shade, wonders, ‘What the doose can be keeping Maria,’ until that estimable lady makes her appearance, followed by a shopman bending like Atlas under his load of boxes and parcels. Brian disliked shopping quite as much as the rest of his sex, but being a lover, of course it was his duty to be martyrised, though he would not help thinking of his pleasant club, where he could have been reading and smoking with something cool in a glass beside him. After Madge had purchased a dozen articles she did not want, and had interviewed her dressmaker on the momentous subject of a new dress, she remembered that Brian was waiting for her, and hurried quickly to the door.

‘I haven’t been many minutes have I, dear?’ she said touching him lightly on the arm.

‘Oh dear no,’ a

nswered Brian, looking at his watch, ‘only thirty—a mere nothing, considering a new dress was being discussed.’

‘I thought I had been longer,’ said Madge, her brow clearing, ‘but still I am sure you feel a martyr.’

‘Not at all,’ replied Fitzgerald, handing her into the carriage, ‘I enjoyed myself very much.’

‘Nonsense,’ she laughed, opening her sunshade, while Brian took his seat beside her, ‘that’s one of those social stories—which everyone considers themselves bound to tell from a sense of duty. I’m afraid I did keep you waiting—though, after all,’ she went on with a true feminine idea as to the flight of time, ‘I was only a few minutes.’

‘And the rest,’ said Brian, quizzically looking at her pretty face, so charmingly flushed under her great white hat.

Madge disdained to notice this interruption.

‘James,’ she cried to the coachman, ‘drive to the Melbourne Club. Papa will be there, you know,’ she said to Brian, ‘and we’ll take him off to have afternoon tea with us.’

‘But it’s only one o’clock,’ said Brian, as the Town Hall clock came in sight. ‘Mrs Sampson won’t be ready.’

‘Oh, anything will do,’ replied Madge, ‘a cup of tea and some thin bread and butter, isn’t hard to prepare. I don’t feel like lunch, and papa eats so little in the middle of the day, and you—’

‘Eat a great deal at all times,’ finished Brian with a laugh. Madge went on chattering in her usual lively manner, and Brian listened to her with delight. It was very pleasant, he thought, lying back among the soft cushions of the carriage, with a pretty girl talking so gaily. He felt like Saul must have done when he heard the harp of David, and Madge with her pleasant talk drove away the evil spirit which had been with him for the last three weeks. Suddenly Madge made an observation as they were passing the Burke and Wills monument, which startled him.

‘Isn’t that the place where Mr Whyte got into the cab?’ she asked, looking at the corner near the Scotch Church, where a vagrant of musical tendencies was playing ‘Just Before the Battle, Mother ‘ on a battered old concertina in a most dismal manner.

The Crowned Skull

The Crowned Skull Madame Midas

Madame Midas The Opal Serpent

The Opal Serpent The Solitary Farm

The Solitary Farm The Mystery Queen

The Mystery Queen The Bishop's Secret

The Bishop's Secret Red Money

Red Money The Red Window

The Red Window The Pagan's Cup

The Pagan's Cup The Third Volume

The Third Volume A Coin of Edward VII: A Detective Story

A Coin of Edward VII: A Detective Story Hagar of the Pawn-Shop

Hagar of the Pawn-Shop The Millionaire Mystery

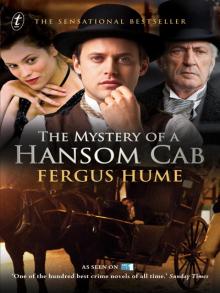

The Millionaire Mystery The Mystery of a Hansom Cab

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab